Questions about Tone

Recognition of tonality is one of the tests in the Willems® Diploma for Music Education.

I’ve always wondered about this subject.

- Why do composers prefer this or that key?

- Musicians describe tonalities as more or less light, dark, serene…

- So what about transpositions?

To try and answer these questions, I’m going to consider several points of view that I think it would be interesting to compare.

In the end, these questions remain open to your contributions and comments…

First of all, a brief look at two types of musical ear, distinct in nature but complementary in the way they function: the absolute ear and the relative ear.

The absolute ear

The ‘absolute ear’ in music is characterised by the fixed association between the pitches of sounds and the names of notes, which requires people with this absolute ear to hear the names of notes as soon as the sound has a musical structure (in terms of harmonics). As I don’t have this ability myself, I’m in no position to talk about it. I can only describe what the ‘chosen ones’ tell me!

‘Elected’? Yes, a priori, because this automatic and instantaneous labelling of sounds by their names is a definite advantage for musical dictation and key recognition. Up to a point…

Because the pitch has evolved over the centuries, and continues to climb.

From 415 Hz in the time of J.-S. Bach, it was fixed at 440 Hz at the beginning of the 20th century, rising to 442 and even 444 Hz in philharmonic orchestras, a difference of more than 1/2 tone.

So what about tonality? The famous tonal colour that distinguishes between Eb Major and D Major when this Eb will be heard as D and D will sound C# at Baroque pitch (more or less)?

The relative ear

The “relative ear” is more important to the musician than the absolute ear, because it is inseparable from the relationships between sounds, whereas the absolute ear simply labels successive series of sounds separately.

Mozart is often quoted as saying: “Music is not in the notes but between the notes”.

All the introductory work and then the musical training proposed by Edgar Willems is geared towards the development of aural relativity. The absolute labelling of sounds is not specifically sought, but it is not ruled out. This is why, as soon as a sung sound is named, it is named at its absolute pitch (by checking with an instrument or a tuning fork), unlike the “Tonicado” method in which C designates the first degree of the scale whatever its pitch.

The battle between the absolute and the relative

Why try to recognise a key in absolute terms, given that the relationship between note names has changed over the centuries?

Jacques Chapuis’ proposal

The core of the thinking and pedagogical practice proposed by E. Willems is based on the comparison of musical phenomena, echoing the various aspects of human nature (to leave Teillard de Chardin’s expression of “Human Phenomenon”). Willems defined himself as a “phenomenologist” whose observation was not limited to the dissociation of musical phenomena into simple elements. He extensively studied and presented the relationships and associations (good and bad) that link these elements together.

To recognise tonalities, J. Chapuis suggests combining the two types of ear.

See “Éléments Solfégiques et Harmoniques du Langage Musical” p.39 to 43 published by Pro Musica.

From the tonic that emerges from hearing a work, we sing the chord, which enables us to determine its mode, then we add to these 3 sounds the A of the diapason (at 440 Hz), which gives a pattern of 4 sounds, different for each of the 24 keys.

From this A, we then diatonically sing the notes of the degrees that bring us back to the tonic, creating a second pattern that completes the first, again in a unique way for each of the 24 keys.

This ‘ethos’ of tonalities, as he calls it, does two things:

– Distinguish and compare keys.

– Identify the key in relation to the A of the tuning fork (440).

This work of recognition, practised first by singing aloud and then in inner hearing, has the merit of developing and strengthening this inner hearing, with the possible aim of acquiring absolute hearing of the tonalities (relative, however, to the pitch chosen: 440).

What about recognising tones by their ‘colour’?

Another question is that of being directly sensitive to the colour of a tone, or at least to the particular character induced by one tone in relation to another.

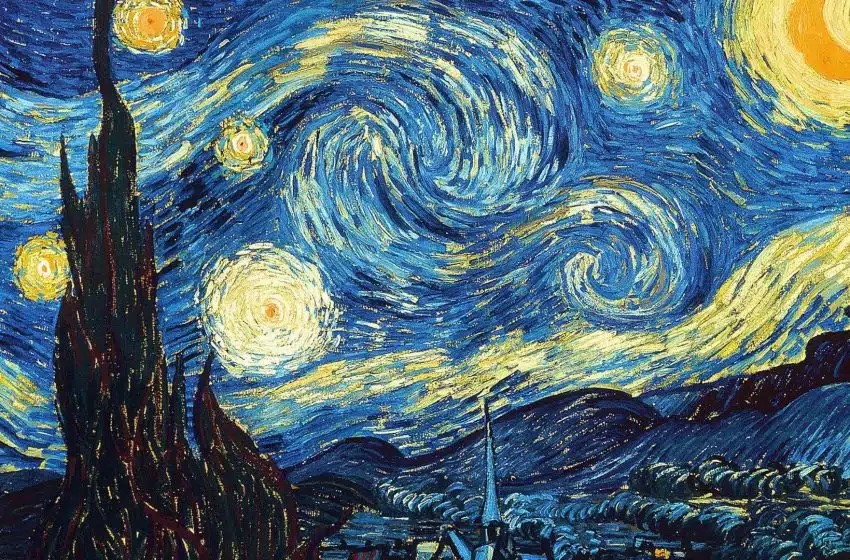

I shared in l’écoute musicale n°16 devoted to Messiaen a fascinating article on his particular relationship to sound and colour. Apart from the fact that this correspondence varies even between musicians gifted with sinesthesia, it would seem that Messiaen uses an extremely rich vocabulary to describe colours, and thus allows comparisons to be made, which brings us back to the ‘relative’ rather than the ‘absolute’ dimension of the perception/reception of music.

Having noted this relativity between colours (mainly chords for Messiaen, … if I’ve understood correctly!) and keys, what happens if we don’t recognise these differences?

When analysis of the phenomenon kills the phenomenon

What about the poor neophyte who listens to J.S. Bach’s Mass in B minor without knowing that it is in B?

And what if he listens to it with a recording from the 1990s at pitch 440, by Sergiu Celibidache?(https://youtu.be/l2NapDhXUb0) or a recent (dare I say modern!) recording played on period instruments at pitch 415, by Philippe Herveghe for example.(https://youtu.be/F57cxiB6jKQ)? Not to mention the differences in tempi, phrasing and so on…

If you had to be sensitive to tonality to appreciate such a monument to the history of music, very few would be able to benefit from it…

Fortunately, music is a universal language that needs no explanation to be heard, received and appreciated.

Studying a work and analysing it in depth generally leads to a greater appreciation.

That is, of course, on condition that you return to listening to the work as a whole, because the analytical breakdown can turn into a deadly dissection!

This is another distinctive feature of E. Willems’ teaching approach: starting from the Whole and returning to the Whole.

There remains a question about tonality

Why did J.S. Bach choose the key of B minor for this Mass, which he worked on all his life?

Wouldn’t it have been simpler to write it in C minor?

And why are certain keys preferred for certain works, often D minor for the Requiem, for example, or simply preferred by certain composers?

And what about Schubert’s lieder cycles transposed into different keys to suit the different registers of the performers?

And what about the practice of transposition that Dinu Lipatti preached to his students, who, according to Jacques Chapuis, could transpose his entire repertoire in any key at any tempo!

I won’t answer that question, which is beyond my remit, but I’m curious to read your contributions in the comments to shed some light on the matter…

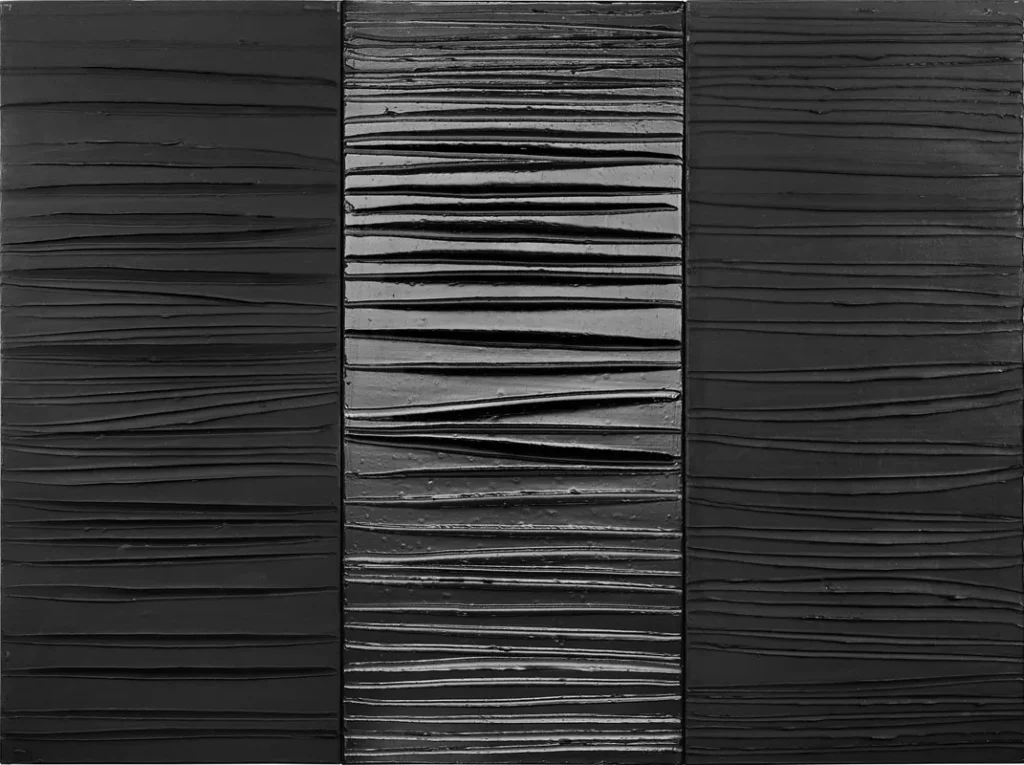

Finally, here are two illustrations of the relationship to colour by painters Serge Poliakoff “Composition abstraite” (1967) and Pierre Soulages ” (2009).