The place of songs in music education

Songs have always been central to Willems® music education.

Because they are a synthesis of musical elements – rhythm, melody and harmony – combined with a text that the music enhances, songs make it very easy to realise that music is a language.

Secondly, removing the words and replacing them with a vocalise encourages experimentation with the expressive qualities of melody, even without words, and helps to develop a sense of melody.

Choice of repertoire

The Willems® training recommends using different types of repertoire in lessons, to cover the needs of music education over time. There are 6 different and complementary genres, and a song can be found in several genres simultaneously:

- Songs of 2 to 5 notes, to encourage the right intonation within a restricted and easily transposable range;

- Songs that encourage rhythmic development, in particular by striking the 4 rhythmic modes;

- Songs for the names of the notes, either integrated into the text like onomatopoeia, or easy to solfy to move towards awareness and oral automatism;

- The songs known as “interval” and “chord” for their recognition;

- Canons and songs in 2 voices to introduce and develop a sense of polyphony and harmony:

- Traditional songs for their historical and cultural dimension.

Traditional songs

Traditional songs are often considered “old-fashioned” and neglected.

Personally, I’ve always defended the traditional French repertoire, because it fed my childhood through the records in the “Le petit ménestrel” collection, which I knew by heart.

So I found it normal to sing “Malbrough s’en va-t-en guerre”, “La mère Michel”, “A la claire fontaine”, and so on, and to teach them to my young pupils in order to maintain the tradition, justified by explanations of the text to the first degree.

On the other hand, I was rarely seduced by contemporary children’s songs, which I often found bland and watered-down.

Other types of directory

Another repertoire that is widely used in schools, for various reasons that are not always good, are songs of more or less exotic origin, with lyrics assimilated to onomatopoeia that are poorly translated and enhanced by syncopated rhythms.

I can understand the appeal of learning a song proposed by a child of foreign origin. It’s a good opportunity to enhance the child’s native culture and help them integrate. You could even ask them to look for such a repertoire that has not been handed down by their family. Promoting this repertoire also promotes the child who brings it and helps to open up others to this other culture.

In the same vein, songs in a foreign language can be suggested by the teacher.

I have fond memories of a programme of Christmas songs at Ryméa in 9 or 10 languages!

Language teachers know all too well that songs are a great way of learning.

Cultural minorities also know that the sung tradition is a very good refuge for a language threatened with extinction.

The educational use of these different repertoires depends largely on the context in which they are practised: nursery and primary schools do not have the same objectives as music schools, both of which generally compensate for the loss of the singing tradition in families.

Societal developments

The war in Ukraine and the #metoo movement have radically changed my view of traditional repertoire.

The French traditional repertoire is naturally a reflection of its history, praising above all the exploits of warriors and revolutionaries, more rarely the humanity of an “Anne de Bretagne”.

And that history is a bloody one!

That didn’t stop me in my early days in Paris from teaching my pupils the song “Jean Bart”, the valiant privateer “killing, hanging, decapitating (the English) without even failing for a moment!” But what a magnificent melody!

Nor to defend “Malbrough” on the pretext that this song tells and develops a hoax intended to give courage to the French against these same English…

I understand (finally?) today that these songs and explanations contribute to trivialising and embellishing these barbaric acts.

These stories should be learned in history lessons, not in music lessons given to children.

Human nature is complex, and the “dark side of the Force”, always present somewhere, must be unmasked and fought.

So songs describing and denouncing negative or violent behaviour should retain a small place in this repertoire.

“I’ve got good tobacco” is a good illustration: “I’ve got good tobacco, you won’t have any! How selfish!

As a bonus, we can explain the old tradition of snuff, still used in some countries, and tragically replaced by another white powder… Well, that’s still debatable!…

The #metoo movement has triggered a global awareness of the violence perpetrated against women by an all-powerful patriarchy.

The latter can no longer be valued, or even simply tolerated. This oppressive over-power must be fought.

This starts with dismantling and denouncing sexist discourse.

In children’s songs, you have to be vigilant about the place of the mother and the role she plays.

And I’m not talking about the many innuendoes of a second-degree reading, very often saucy or political, such as “Nous n’irons plus au bois” (which denounces the closure of brothels by Louis XIV) or “Le bon roi Dagobert” written by the Sans-culottes to make fun of Louis XVI under the guise of Dagobert, a distant king of the 7th century who was absent-minded and a bon vivant.

While “A la pêche aux moules” warns young girls against being attacked by the boys of the town, “Il pleut bergère” (It’s raining shepherdess) is much more respectful: the boy, full of anticipation, announces that he is going to ask his father for her hand in marriage (but this is a gallant song by a well-known author: Fabre d’Églantine).

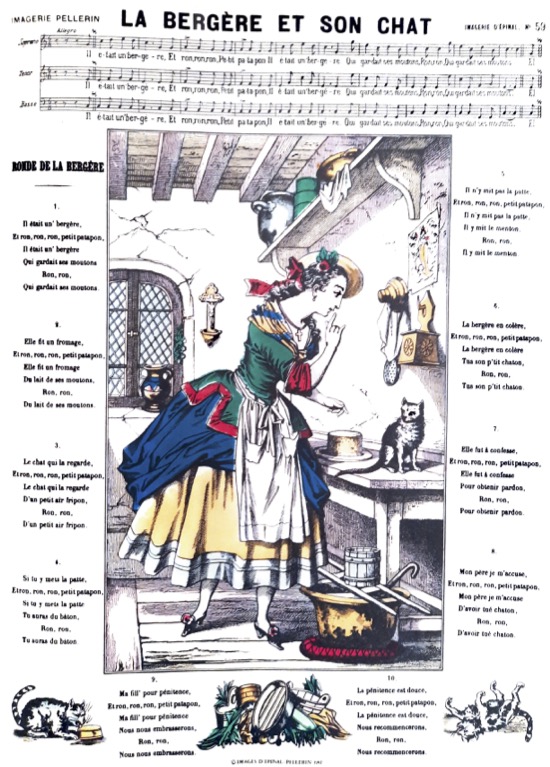

But what about the last verses of “Il était une bergère” when the priest, as a penance, offers to kiss the shepherdess who is willing to start again?…

On this subject, see the article “Comptines pour enfants, un double sens réservé aux adultes“.

Conclusion

The repertoire of children’s songs is vast enough to draw from it those that will nourish children’s imaginations and develop their poetic as well as melodic sense. For the most famous songs, you can avoid the dubious stanzas, and you don’t have to interpret “Au clair de la lune” from an erotic angle…

There are also many beautiful songs to be discovered in the contemporary repertoire.

And why not compose some yourself?

In all cases, I would urge you to study the texts of teaching songs closely, to ensure that each word sung by the children is understandable, i.e. can be explained and explained, which will help to enrich their vocabulary, and in the case of traditional songs, to do some research to find out about their origins and choose them with full knowledge of the facts.

Finally, here’s a wonderful song adopted by a great Argentinian musician-poet, Atahualpa Yupanqui: “Duerme negrito”. It is a good illustration of what I wanted to say in this article: the tenderness of the lullaby, the hard work of the working woman, the threat of the white boss, the dreams she prefers to pass on to her child…