Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915)

“Art is just a means of intoxication,

a wonderful wine.”

Scriabin

Alexander Scriabin is one of the most original figures in 20th-century Russian music. Less played today, he was, in his day, a more important composer than Tchaikovsky.

The young Scriabin experienced his first musical shocks thanks to the music of Chopin and Wagner. Later, he became interested in Debussy, Ravel and Richard Strauss, before realising that classical harmony had had its day. He thus proposed his own musical language, with one goal in mind: to create a total work of art that would lead listeners to a form of ecstasy.

Alexander Scriabin was an excellent pianist. He wrote extensively for his instrument and, for example, his Etude in D sharp minor became very famous.

Alexander Scriabin was a master of the grand free form and also a virtuoso of the miniature.

In Russia during the 1910s, Alexander Scriabin was considered the leader of the modernist movement.

I find the evolution of his musical language fascinating. That is what I want to share in this article…

Short listening samples marking his stylistic evolution

Studies for Piano: Op. 2 – 1889 / Op. 8 – 1894 / Op.42 – 1903 / Op. 65 – 1912

Op. 2 No. 1 in C♯ minor:Andante – Op. 8 No. 12 en D♯ mineur: Patetico – Op. 42 No. 3 in F♯ major: Prestissimo – Op. 42 No. 4 in F♯ major: Andante – Op. 65 No. 3: Molto vivace

By Vladimir Horowitz (1968 live Op.8 – 1972 studio, the others)

Sonatas – Excerpts from 3 periods:

- 1892: Romantic inspired by his model Chopin, Sonata No. 1 Op. 6

1st Movement (of 4) Allegro con fuoco – by Vladimir Ashkenazy - 1907: More personal language, Sonata No. 5 Op. 53 in F# Major,

Allegro – Presto con allegrezza Meno – by Sviatoslav Richter - 1912: Modern and mystical, Sonata No. 9 Op. 68 “Black Mass” – by Pierre-Laurent Aimard

Concerto et musique symphonique

- Concerto for Piano and Orchestra Op. 20 (1896-97), 1st Movement (Allegro) (7’50)

- Rêverie, Op. 24 (1898) (4′)

- Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 43 – ‘Le Poème Divin’: 3. Jeu Divin (Allegro – vivo – allegro) (9’53)

- Mystérium – Introduction (Lent. Impérieux) (6’25)

Long listens

Symphony No. 2 * in C minor, Op. 29 (1901)

00:00 – I. Andante 05:42 – II. Allegro 14:59 – III. Andante 26:36 – IV. Tempestoso 32:05 – V. Maestoso

Performed by the Scottish National Orchestra, conducted by Neeme Järvi.

Mysterium * (completed by Alexander Nemtin)

I. Universe

By Michel Tabachnik, conductor – Susan Narucki, soprano – Håkon Austbø, piano – North Netherlands Orchestra – North Netherlands Concert Choir. Live recording from 2006.

Works for Piano

Sonata No. 2 in G sharp minor (Sonata-Fantasy) Op. 19 (1895-97)

1. Andante – 2. Finale : Presto

By Evgeny Kissin (2022)

Poème-Nocturne for piano, Op. 61 (1911-12).

By Sviatoslav Richter, Piano (1993)

Sonata No. 9, Op. 68 “Black Mass” (1912-13)

By Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Piano

Two Dances * Op.73 (1914)

No. 1 ‘Garlands’ & No. 2 ‘Dark Flames’

By Vladimir Sofronitsky, Piano (1960)

Five Preludes, Op. 74 (1914)

I. Painful, heart-rending – II. Very slow, contemplative – III. Allegro drammatico – IV. Slow, vague, indecisive – V. Proud, bellicose

By Emil Gilels, Piano (1984)

Symphonic works

Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in F sharp minor, Op. 20, (1896-97)

By Peter Jablonski, Piano · Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin · Vladimir Ashkenazy, conductor (1996)

1. Allegro

2. Andante

3. Allegro

The 3 movements by Vladimir Ashkenazy, Piano – London Philharmonic Orchestra, Lorin Maazel, Conductor (1971)Conductor (1996)

Rêverie, Op. 24 (1898)

By Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin · Vladimir Ashkenazy, Conductor.

Le Poème de l’Extase, Op. 54 (1904-07)

By Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin · Vladimir Ashkenazy, Conductor.

Prometheus or The Poem of Fire * Op. 60 (1908-10)

By Anatol Ugorski, Piano – Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Boulez – Chicago Symphony Chorus, Duain Wolfe

Comparative listening corner

Towards the Flame: Poem for Piano, op. 72, (1914) *

Vladimir Sofronitsky (1946)

Grigory Sokolov (1973)

Michael Ponti (1974)

Arcadi Volodos (2005)

Andrei Korobeinikov (2008)

Heinrich Neuhaus (1951)

Vladimir Horowitz (1974)

Sviatoslav Richter (1994)

Igor Zhukov (1980)

Alexandre Kantorow (2022)

* To find out more…

Evolution of his musical language

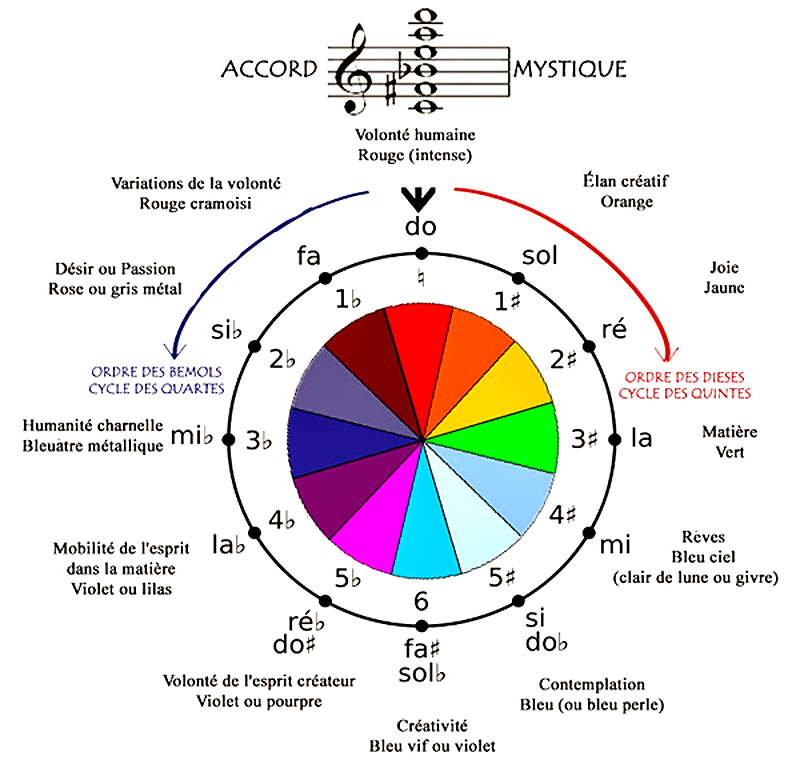

In his early years, he was greatly influenced by the music of Frédéric Chopin and wrote works in a relatively tonal late Romantic style. Later, and independently of his highly influential contemporary Arnold Schoenberg, Scriabin developed a substantially atonal and much more dissonant musical language, which was in keeping with his personal brand of mysticism. Scriabin was influenced by synesthesia and associated colours with the different harmonic tones of his atonal scale, while his colour-coded circle of fifths was also influenced by theosophy. He is considered by some to be the leading Russian symbolist composer.

Towards the Flame: Poem for Piano, op. 72, (1914)

Here are two (anonymous) introductory texts taken from YouTube:

Like Liszt, Scriabin transposed his philosophical concerns and mystical quest into his compositions. Influenced by theosophy (a doctrine drawing on Eastern religions, philosophy and Greek myths), he saw music as a means of accessing the divine. According to him, the world would be transfigured by a purifying fire, an idea that inspired the symphonic score Prometheus, the Poem of Fire (1908-1910) and Towards the Flame, the last of his works entitled Poems.

Following in the footsteps of Liszt, Wagner and Debussy, this piano piece dissolves tonality. Hypnotic repetitions vibrating with trills, tremolos and repeated chords are accompanied by variations that drive the discourse forward. The progression, punctuated by expressive indications that mark its stages (‘sombre’, ‘with nascent emotion’, ‘with veiled joy’, ‘increasingly animated’, ‘with increasingly tumultuous joy’), leads to an ecstatic climax, to be played ‘like a fanfare’.

…

Towards the Flame is one of the last piano pieces composed by Alexander Scriabin in 1914. The melody of this work is very simple, consisting mainly of descending semitones. However, the unusual harmonies and difficult tremolos create an intense and fiery luminosity. This piece was intended to be Scriabin’s eleventh sonata, but he had to publish it earlier than planned for financial reasons. This is why it is simply titled ‘poem’ and not ‘sonata’. According to the famous pianist Vladimir Horowitz, this piece was inspired by Scriabin’s eccentric belief that a constant accumulation of heat would eventually cause the destruction of the world. The title of the piece reflects the fiery destruction of the Earth, as well as the constant emotional build-up and crescendo throughout the piece that ultimately leads “towards the flame”.

Here is also an excerpt from an interview with Vladimir Horowitz in 1974, transcribed from English:

…”But he was the father of modern piano, the father of pianism and the father of sonata form. Extraordinary. Extraordinary.

That’s why I’m so interested in it. If the musician has a gift, I’m not interested in him, or in a percentage of his music or anything else. I just know it’s good music.

So he was interested in Clementi, and at that time, there was only Clementi, yes. Scriabin, he also thought was difficult for the public to understand. That’s why he was reluctant to play much, but he played Scriabin a lot.

Scriabin was a mystic at the end of his life. And in his imagination, he thought that one day the heat would destroy the world. He believed that, he didn’t know that the atom could even be invented at that time.

It was composed in 1912. The title of this work is Towards the Flame. It’s very modern, very percussive. It’s very crazy. It’s very difficult to grasp. And it’s a very exciting work. Yes, I have to take the jacket. It’s a difficult work. It’s very special. It’s very special music. It’s a more percussive piano.

It’s a bit scary music. Prepare yourselves for a powerful sound. If I don’t collapse, it’s fine.

All right, let’s go. It’s difficult. Yes, it is.”

Then he takes off his jacket, sits down at the piano, and plays the piece, finishing with a burst of laughter and saying, ‘It’s difficult!’…

Prometheus or the Poem of Fire, Op. 60

Prometheus or the Poem of Fire, Op. 60 for piano, choir, large orchestra and ‘luce’, a type of colour organ designed to create the synesthetic effects desired by the composer.

Wikipedia on the chromatic organ: “The part for the chromatic organ is notated on a separate staff, in treble clef at the top of the score, and consists of two parts: one changes with the harmony and always moves towards the fundamental note of the dominant harmony, thus producing the colour that Scriabin associates with each key; the other consists of much longer notes, sustained over several bars, and does not seem to be related to the harmony (nor therefore to the first part), but rises slowly up the scale, one tone at a time, with the changes spaced several pages apart in the score, or a minute or two apart. The relationship between this part and the first part, or with the music as a whole, is unclear.

The score does not explain how two different colours should be presented at the same time during a performance. This part of the colour organ also contains three parts at a given moment in the score.

Sources differ as to Scriabin’s intentions regarding the realisation of the chromatic organ part: many claim that the colours were to be projected onto a screen in front of the audience, but others claim that they were to flood the entire concert hall and that their projection onto a screen was only a compromise adopted after it proved impossible or impractical to flood the concert hall. The score itself contains no indication of how this was to be achieved.

Two Dances Op.73 (1914)

Below is a proposal for the colourisation of ‘Garlands’ by Rob Colley, piano, and Sarah Colley, video, to approximate Scriabin’s visionary ideal in his late period.

Symphony No. 2

“The Second Symphony was completed in 1901, one year after the first. It is the most traditional of his symphonies in terms of formal structure. The first two movements (Andante, Allegro) are played without interruption and structurally form a classical sonata movement. In the third movement (Andante), however, he makes a remarkable step towards the highly chromatic sound associated with the mature Scriabin. The movement opens with birdsong played on the flute, another characteristic feature of Scriabin. The rest of the movement, with its frequent evocations of birdsong and other sounds of nature, is like a long, dreamlike walk in the wilderness. Even the central climax is natural. The fourth movement (Tempestuoso), a scherzo in minor, is a charming movement, full of turbulence in the strings, timpani and brass, interrupted briefly in places by more lyrical passages. Towards the end of the movement, the tonality modulates to major and leads seamlessly into the final movement Maestoso, with a majestic reprise of the symphony’s opening theme. This work marks an important stage in Scriabin’s development as a composer, and still shocked his initial audience somewhat when it premiered in Saint Petersburg under the baton of Anatol Lyadov on 12 January 1902.” – John Dobson

Mysterium : Preparation for the Final Mystery

“There will not be a single spectator. Everyone will be a participant. The work requires special people, special artists and an entirely new culture. The cast includes an orchestra, a large mixed choir, an instrument with visual effects, dancers, a procession, incense and a rhythmic textural articulation. The cathedral in which it will take place will not be built of a single type of stone, but will change continuously according to the atmosphere and movement of the Mysterium. This will be achieved with the help of mists and lights, which will alter the architectural contours.” Alexander Scriabin

The great synaesthetic oratorio Mysterium was completed, arranged and orchestrated by conductor and composer Alexander Nemtin (1936-1999) from Scriabin’s 72-page sketches into a three-part concertante work entitled Preparation for the Final Mystery.

I. Universe

II. Man

III. Transfiguration

The project (excerpt from Wikipedia article)

… Scriabin wanted this piece to appeal to all the senses (through devices such as his “light keyboard” or other lesser-known devices often devised by the musician himself, as well as rituals, dances and caresses (even sexual relations), with the audience playing an active role in the ceremony. The performance of this piece, whose mystical and philosophical aspirations are linked to the theosophical theories in which Scriabin had taken a keen interest during the last fifteen years of his life, was to be followed by the disappearance of humanity (or even the universe) in ecstasy and its replacement by more ‘noble’ beings…

If you would like to listen to the entire 2½ hours of this titanic work without interruption, here is the YouTube link:

https://youtu.be/xT92SvAIobY?si=oSVYhFPbVRwFUJO3

Stanislav Kochanovsky, conductor Alexander Ghindin, piano Nadezhda Gulitskaya, soprano Hungarian Radio Choir Belgian National Orchestra / Public concert recorded in 2018 in Brussels.