The development of the musical ear and singing in Willems® music education

Mateja Tomac Calligaris – Willems® Didactic Dissertation

Here is the dissertation written in 2023 for her Willems® Didactic Diploma by my former colleague Mateja Tomac-Calligaris. She wrote her dissertation on “The development of the musical ear and singing in Willems® music education“. She has very kindly agreed to have it published here and made available to students and amateurs of music pedagogy. Thank you very much!

Move your mouse over the red headings in the Table of Contents and click on the highlighted blue one to go directly to the corresponding chapter, and on the arrow at the bottom right to go to the top of the page.

The development of the musical ear and singing in Willems® music education

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The ear and the voice are extremely important to everyone, especially those involved in music.

The ear has a special place among the five human senses, since sound is perceived directly, at a distance, rapidly and has a strong impact on human beings. From a physiological point of view, the ear remains rather mysterious and listening is not its only function.

The ear, as the organ that transforms acoustic vibrations – through complex mechanisms – into sound in the brain, is closely linked to the voice, the primary means of human expression.

Willems focused above all on the basic principles of musical education.

He advocated an approach that takes into account the human being in his or her totality, i.e. in his or her physical, emotional and mental dimensions, as part of a whole comprising a material pole and a spiritual pole. In music, this trilogy corresponds to rhythm, melody and harmony. Music is the art of sound, and the development of the musical ear and musical expression, especially singing, is central to Willemsian thought. The development of the ear enables the musician to develop the inner image of sound, which is the key to true musicality.

In the remainder of this dissertation, I shall therefore concentrate on the teaching principles advocated by Willems for the development of the musical ear and singing.

My main activity is managing a music school, which covers a very rich and varied field. As a result of my many experiences in this field of work, I’ve come to the conviction that it’s very important never to lose sight of the basics of how music works – the musical ear and singing. This is why I have chosen to study this pedagogical subject in greater depth.

I will confine myself mainly to the beginnings of music education and present the basic principles of pedagogical work. I will add a few personal experiences and insights to Willems’ thoughts. But first of all I will present the phenomenon of sound and the basic mechanism of human perception of sound.

ACOUSTIC VIBRATION AND SOUND

Sound is a sensation caused in humans or animals with hearing by the vibration of material bodies/things. When the vibration, propagated through the air or another elastic body, reaches the human ear, the sense of hearing, which is connected to the brain, creates the sensation of sound in us by means of a complex mechanism that I will discuss briefly later. The ripple itself is an objective phenomenon, whereas the sensation is subjective; it depends on the constitution of the auditory organ, previous experience of sound, interest in sound, neuronal connections, etc. The ripple itself is an objective phenomenon, whereas the sensation is subjective; it depends on the constitution of the auditory organ, previous experience of sound, interest in sound, neuronal connections, etc.

Sound waves are defined above all by the frequency and amplitude of the vibration. In brief and simplified terms, we can say that the pitch of the sound depends on the frequency, while the volume of the sound is determined by the amplitude of the wave. The timbre of the sound is the result of the shape of the sound wave. From the point of view of its production, the timbre of sound depends on the construction and shape of the body emitting the vibrations and the way in which they are set in motion, or even amplified; these conditions also have an impact on the duration of the sound.

The human ear picks up frequencies between 16 and 20,000 Hz, but more sensitively between 2,000 and 5,000 Hz; below the lower limit we have infrasound, above the upper limit we have ultrasound. Animals of different species have different sound perception radii.

For music, we use sounds with frequencies between 65 and 8276 Hz.

THE EAR AS A PHYSIOLOGICAL ORGAN

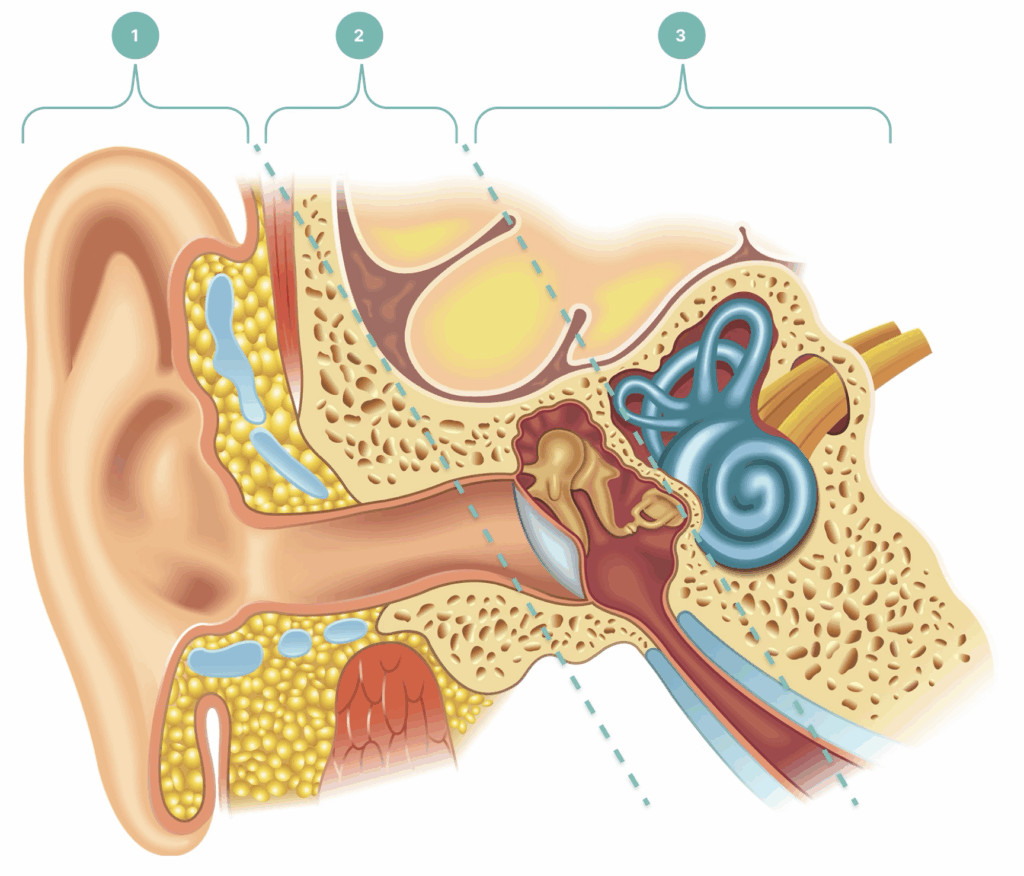

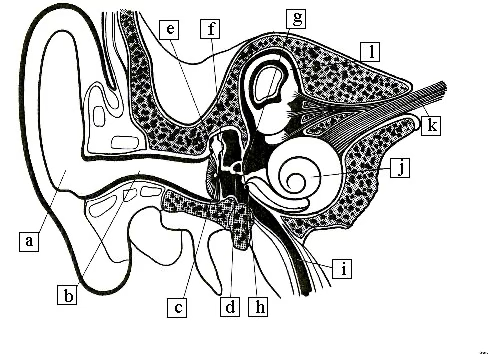

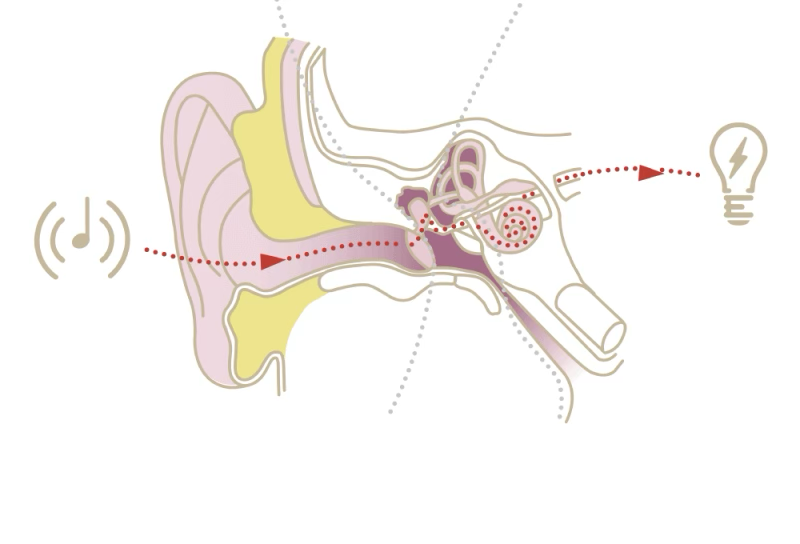

The ear, an organ designed to receive sound, also plays an important role in maintaining balance, perceiving the body in space and maintaining body posture. It is made up of 3 parts: the outer (1), middle (2) and inner (3) ear.

The outer ear comprises the auricle (a), which picks up sound waves, and the auditory canal (b), which is just over 2 cm long and acts as a resonator. The auditory canal is best at amplifying sounds of the frequencies used in human speech. The outer ear is separated from the middle ear by the eardrum (c), an elastic fibrous membrane and connective tissue.

The three ossicles are the smallest bones in the human body.

Assembled in a chain like a flail, they form part of the middle ear: the hammer (e), the anvil (f) and the stirrup (d). Attached to them are the smallest muscles in the human body, which – through their contraction and relaxation – balance the volume of the sound transmitted, either by amplifying it under the effect of the flail, or by reducing it by inhibiting the muscles that enable them to move.

The malleus is attached to the eardrum, while the stirrup is attached to the oval window (h) of the cochlea (j), the equivalent of an eardrum in the inner ear. In the middle ear we also find the Eustachian tube, which connects the ear to the oesophagus. It regulates air pressure in the middle ear.

The inner ear comprises the auditory organ, the cochlea, lined with hair cells, nerve cells, and the balance organ with the three semicircular canals.

Thus, the 3 parts of the ear correspond to 3 states of vibration

- it first propagates in the air, a gaseous medium, with the pinna playing an initial role of concentration and amplification

- in the middle ear, the vibration is transformed and amplified by the mechanical movement of the chain of ossicles;

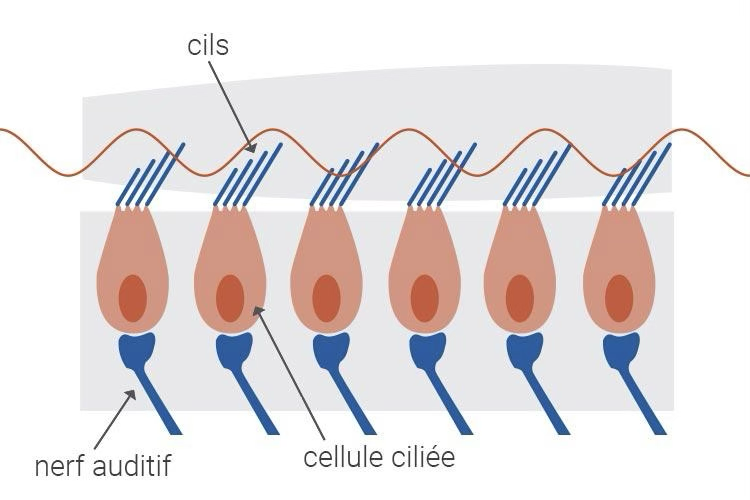

- finally, this mechanical impulse is transmitted to the liquid medium of the inner ear, creating a wave in the cochlea lined with hair cells, the more or less strong undulation of which creates an electrical signal that the auditory nerve transmits to the brain.

It should be noted that hair cells are fragile.

If the wave is too violent, they risk being permanently damaged, if the brain has not instructed the muscles of the ossicular chain not to reflect a wave that is too strong. In this case, hearing loss can result from the inappropriate use of headphones stuck to the ears…

So the vibration travels through the ear canal to the eardrum, which oscillates. The undulation is transmitted to the chain of ossicles in the middle ear. Given the composition of the middle ear, the intensity of the vibration is greatly amplified for frequencies between 1 and 10 kHz. The amplified mechanical force is converted into electrical signals when it hits the liquid in the cochlea. On the basilar membrane of the cochlea are all the cells that are fundamental to our prehension and vibration analysis, the organ of Corti, named after its discoverer Alphonse Corti. These hair cells are mechano-electrical transducers, which transform the movements of the cell cilia into electrical signals in the cells. The electrical signals pass through the cochlea and continue along the auditory nerve to the brain, which finally transforms this nervous coding into an image called SOUND!

It is only in the brain that SOUND is produced and analysed.

All the previous stages only convey VIBRATIONS.

It is invaluable for music educators to have a good understanding of the physiological functioning of the ear, because the only way they can encourage their pupils’ hearing development is by influencing the functioning of the middle ear and the way the brain analyses sound.

In fact, the presence of inervated muscles linked to the ossicular chain means that the brain can act on their reactivity. How can it do this? By focusing attention, by ‘putting your ear to the ground’!

The educator then acts by encouraging the pupil to listen, to take an interest in sound, and even to like musical sound…

THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE MUSICAL EAR

Willems has spoken a great deal about the ear and auditory development. To fully express the synthesis of his thought, he used the expression musical ear. The musical ear enables human beings to receive and understand music. Here, too, we come across the trilogy that represents the foundation of Willemsian thought: body – emotions – thought. In my opinion, the inestimable value of Willems’ work lies in the identification of these three constituent elements of the human being – physical, emotional and mental – and their correlation with the three constituent elements of music: rhythm, melody and harmony.

Physical and physiological life corresponds to rhythmic life;

emotional life corresponds to melodic life;

and mental life corresponds to harmonic life.

| Life | Sensory | Affective | Mental |

| Music | Rhythm | Melody | Harmony |

In his conception of the musical ear, Willems combined the ear as a physiological organ with the ‘inner’ ear, which comprises all the mental functions linked to the musical content in our memory. With these mental functions, the musician can create inner auditory images, which are the key to true musicality.

Here’s one of Willems’ best-known quotes:

‘Bad musicians don’t hear what they’re playing; average musicians could have heard, but don’t; those who are a little better hear what they’ve played, but only good musicians hear what they’re going to play’. (Psychological Bases of Musical Education, Chapter IX – Absolute and Relative Inner Hearing)

Can the musical ear be developed, and if so, how?

This is an essential question for every music educator.

Willems based his pedagogical principles on the conviction that this is entirely possible. Through the experiences he accumulated throughout his life, he was able to confirm this conviction – he talks about it at length in his works. As I’ve already mentioned, the ear is not just a sensory organ, but also includes emotional and mental processes, which change as man evolves. It has great potential, which we can make the most of if we are guided by an interest in music, emotional sensitivity and intelligence.

We can’t change the auditory organ, but we can greatly improve the way it works. This is what “auditory development” is all about.

In his work, Willems explains that the overall ability to listen is conditioned by three more specific abilities: auditory sensory receptivity – the physiological perception of sound through the ear; auditory sensitivity – the emotional reaction to what we are listening to; and auditory intelligence – analytical, conscious listening. In this sense we can use three expressions: hearing – listening – hearing. These three faculties are obviously intertwined, but each has its own qualities and potential for development.

The music teacher needs to know how to develop each area individually, as well as the overall ability to listen, which is affected by other factors – personal characteristics, musical culture, the individual’s relationship with sound and music.

Willems says that musicians have excellent listening skills when they clearly perceive sound information that comes to them from outside, when they react to this information emotionally and when they are able to make conscious what they have heard.

Auditory sensory receptivity

Auditory sensory receptivity enables us to establish contact with sound and sound phenomena. It is a faculty of the ear that recognises and distinguishes different qualities of sound – timbre, intensity, pitch, sound movement, harmonics and so on. Sensory receptivity is our way of using sound material with sensitivity and intelligence.

In his work, Willems has clearly shown empirically that sensory receptivity can be improved. Through education we can encourage, guide and develop the functioning of the auditory organ.

In the 4th chapter of his book ‘The Musical Ear’, Willems quotes Comenius, who said as long ago as 1640: ‘There is nothing to be found in intelligence that has not been arrived at through the senses… The pupil must learn to know sounds, but above all he must learn to use his senses…’.

The five human senses (sight, hearing, touch, smell and taste) are what enable us to make contact with the world around us. Each sense is a special receptor on the surface of the body, exposed to different impacts from the environment, different stimuli. This stimulus may be touch, light, sound, chemical substances in a liquid or gaseous state, etc. We have a different receptor for each of these stimuli. The senses therefore represent a link between man and his environment. Man is capable of perceiving what his senses allow him to; there are many objective elements that remain outside his perception and, of course, his understanding.

The ear is the receptor of sound in humans and is fully developed during gestation, when the child can already recognise different sounds and the voice of its parents in the womb. Immediately after birth, the child takes part in the sound environment, either by listening or by emitting its own sounds, and evolves according to the reactions of those around it.

Willems recognised the importance of developing sensory receptivity in the lives of all musicians and devoted much of his work to it. In his day, receptivity was mostly neglected in music education. Even today, it is often not given the place it deserves in music schools; it is taken for granted or attempts are made to compensate for auditory abilities with development in the cognitive field.

Very often, for example, teachers start to teach pupils to read and write music without their pupils having acquired any concrete aural and vocal experience of sound movement and the different pitches of sounds. Fortunately, the more gifted pupils often make this connection themselves, quite intuitively. They link the content of the different areas of music education that are supposed to work together to understand musical elements correctly. But this doesn’t always happen automatically, far from it, and gaps and weaknesses appear in the musical foundations as a result.

To encourage sensory auditory development, Willems has presented us with a large number of excellent guidelines and recommendations for working with children.

From the very first lessons, children should be discovering, imitating, comparing, valuing and arranging different sounds produced by various sound objects and instruments. The aim is to arouse their curiosity and develop their interest in sound, and even a love of sound. In his work ‘L’oreille musicale’ (The Musical Ear), Willems devotes a great deal of space to the precise description of instruments and their uses, which already enable very young children to acquire experience in the field of sound timbre, intensity and above all the pitch of sounds and sound movement.

Intratonal space and intratonal chimes

His proposals included various sound objects such as bells, calls, whistles, singing tops and also specific instruments of high didactic value such as the slide flute, the siren, sound pipes, etc. Willems also explored intratonal space, a term he coined – he was very innovative in this field. Willems also explored intratonal space, a term he coined – he was very innovative in this area. He had various collections of bells, including a collection of seventeen bells that were tuned to 1/16th of a tone in the distance of a tone. He made a special instrument, the audiometer, with which he managed to produce micro-intervals down to two hundredths (1/200th) of a tone.

Today we use an ‘intratonal chime’ in our music education lessons, with which we can play with micro-differences in pitch. It is made up of 24 metal plates that are visually perfectly identical and are tuned to different pitches in the range from G2 to C3.

This instrument is used in a variety of ways.

In the first degree of initiation, it can be used to produce glissandos, illustrating the upward and downward movement of sound through this intratonal space.

At the second degree, this work is taken further: only a few bars can be fixed to the instrument’s auxiliary case, for example those used to play diatonic or chromatic sequences. When playing with the children, two bars are interchanged when they close their eyes, and they have to re-establish the initial order by listening carefully. This pedagogical principle is called “pre-classification”.

At the third degree, in the ‘classification’ phase, the slides are completely mixed up, and the pupils put them back together, then individually, in the right order. This method is introduced by gradually increasing the difficulty by selecting slides forming increasingly smaller micro-interval sequences.

Willems made intratonal space an important part of music education because ear sensitivity in this area improves not only intonation, but also the ability to perceive vertical musical structures (chords, aggregates, etc.). He established various correlations: those who can perceive an eighth of a tone can also distinguish the two sounds of a harmonic interval; the perception of differences in pitch for a sixteenth of a tone corresponds to the ability to distinguish sounds produced simultaneously in three-tone chords, etc. It is also important to sharpen the ear in the field of vertical musical structures – students listen to and sing the sounds of harmonic intervals, chords and aggregates in isolation.

Auditory sensory receptivity is undoubtedly important as a means of recognising sound, but it is not the most important, since the essence of musical art lies elsewhere. It is certain that auditory sensoriality represents the material basis from which auditory sensitivity and auditory intelligence develop. It is therefore a question of ensuring that sound takes its rightful place in musical education, as the mainstay of musical action. Here we find the three states of the human being: sensoriality for its physical dimension, sensitivity for its emotional dimension, and intelligence for its mental dimension.

Auditory affectivity

Before developing this chapter, we need to define what affectivity is in human nature.

I would say that it is the seat of sensitivity, emotions and mood. All these elements influence human beings by provoking a physical reaction to their environment. Psychologists help their patients by helping to untangle the knots in their relationships. This leads me to associate affectivity with relationships with others, and also with oneself.

Auditory affectivity therefore begins at the moment of our reaction to the sound, which induces a relationship with the sound. It is impossible to define exactly all the nuances of sensation provoked in us by the sound we hear – its timbre, its pitch, its intensity, its duration and also, of course, and above all, by the relationships between different sounds, their distribution in time, their pitches, their duration and the speed with which they are linked together. Add to this inventory the different combinations of personal qualities of the performer, the listener and the composer, their state of mind, and so on. – And yet it occupies a central place in art, touching the human soul where nothing else can, particularly in the art of music.

The heart of affectivity is melody, which begins with the relationship between sounds, and therefore with the interval. Melodic intervals carry a powerful emotional charge. Willems described this at length in the second part of his book ‘The Musical Ear’. He analysed intervals from different points of view: first from a quantitative point of view, then from a qualitative one. The first approach is concerned with the different degrees separating the two sounds in the interval; the second is concerned with the affective value of the interval – consonance, dissonance, etc. The same interval can move up or down and thus have two different qualities. It can be positive or negative, e.g. the ascending interval G-C in G major represents the relationship between a 1st and a 4th degree, potentially a tonic and a subdominant, and is identified as a positive fourth. In C major, this same interval represents the relationship between the 5th and 8th degrees, possibly Dominant and Tonic, and is identified as a negative fourth (fourth as a reversal of the fifth).

The interval has its own expressive meaning, which also depends on the place it occupies in the scale or within the melody; the positive fourth in the previous example often signifies the transition from the tonic to the subdominant, meaning that the tension intensifies and grows; with the negative fourth, on the other hand, the opposite is true: we come from the dominant to fall on the tonic, the tension is resolved and calms down.

The knowledge and recognition of intervals occupies a place of great importance in musical education according to the pedagogical principles of Edgar Willems. One of Willems’ suggestions for working in this area was the use of interval songs. These are songs that begin with a specific interval and their didactic purpose is to teach pupils about the relationships between sounds. The development of the melodic sense, which has a superior role in music, is encouraged in musical education through the repetition and invention of melodic motifs, the enhancement of the expressive potential of intervals, a thorough knowledge of the different modes and scales, melodic improvisation, which is an important element of the inner life, listening to musical literature and, of course, songs sung and performed on instruments.

Singing songs is especially important, since a song represents the synthesis of a rhythm, a melody, a harmony (through their accompaniment) and a story. They offer many possibilities for working in different areas of music education. Songs that pupils have learnt and know well can be sung vocally (without the words) and transposed. Both approaches help to develop melodic memory. A rich and varied immersion is very important.

We must not forget the free melody, the melody that emerges outside traditional melodic tonal structures. We will find them not only in nature, but also in the art of music, especially in contemporary music, which is looking for new possibilities of expression (aleatoric music, electronics, new vocal and instrumental techniques, etc.). In a special way, free melody shifts the point of gravity of musical art to which we are accustomed elsewhere – in other words, it seeks elements of expression outside the structures of the tonal system. All the elements of musical language that are not linked to tonal music can acquire greater meaning (timbre of sound, duration, articulation, expressive value of the interval itself).

Auditory intelligence

Here again, we need to define at least what we mean by intelligence.

Intelligence is the set of processes found in systems, more or less complex, living or otherwise, that enable us to learn, understand or adapt to new situations. Intelligence has been described as a faculty of adaptation (learning to adapt to the environment) or, on the contrary, a faculty of modifying the environment to adapt it to one’s own needs. The acquisition of articulate speech and writing, which help to develop reasoning and abstraction, make human intelligence the benchmark compared with the other kingdoms of nature.

Rather than talking about intelligence, psychologists prefer to talk about higher functions, defined generically as the ability of individuals to understand the relationships that exist between different elements of a situation and the ability to adapt to them in order to achieve their own objectives.

Having aural intelligence means being aware of different elements of musical art – this is of great importance and even indispensable, if we are to be aware of the fact that the essence of art constantly eludes consciousness. For example, we can’t rationally explain what qualifies a work of art as a masterpiece. We can, however, say a great deal about a masterpiece and analyse it: its beauty and value express the whole human being and reflect its creator’s relationship with the world, a relationship that remains largely incomprehensible or inexplicable and mysterious.

In musical education, which follows the principle: unconscious life / awareness / conscious life, this passage from the unconscious to the conscious is precisely the most sensitive point in the process. Thought can actually hinder the spontaneity and naturalness of an act, especially if it is introduced too early. Thought does not come first, it comes later; life exists before thought manages to enter it. Spontaneity means acting without planning or organisation, letting things happen on their own – that’s how life begins.

Rhythmic bodily movement comes directly from life; it is life that gives birth to it and shapes it. We can observe this in animals and also with small children. Thought becomes aware of movement and helps it to become functional. In art, a movement will become even more coherent with the content that the artist wants to convey with the help of thought. If thought intrudes too early or too pervasively, the movement becomes heavy and slow, artificial, no longer linked to the vital impulse – this can happen in our activity, for example in movements linked to instrumental technique.

Our intention, then, is that thought, feeling and action should be fused into a unity that makes it possible to express the material and spiritual dimensions of the art of music in a grand synthesis.

It is very important that auditory intelligence – the ability to name, order and understand the musical content we hear and feel – should not be confused with intellectual knowledge of the musical world. True auditory intelligence enables us to make auditory sensoriality and affectivity conscious; that’s how they become two elements we can use in artistic practice, whether it’s interpretation or creation. Musical reading and writing, theoretical knowledge of harmonic and compositional rules, etc., should not be our goal in themselves, but only means of understanding and expressing musical thought; they must therefore always be linked to sound. It is perfectly possible to “know” a chord without knowing how it sounds and without reacting emotionally to it. It is also possible to compose music on the basis of certain rules, music that is not the expression of man’s inner life. Clearly, this has nothing to do with true art.

Auditory intelligence specifically includes the ability to compare, value, create, associate, analyse, synthesise, remember and imagine creatively.

On the rhythmic level, the process of becoming aware begins with the naming of rhythmic elements (short/long and their combinations). Later, it is the measure that represents the element of awareness, leading from the unconscious act to the reading and writing of music.

In terms of melody, we have two extremely important elements, which Willems deals with extensively in his works: the names of the notes and the degrees of the scale. Of course, we start at the melodic level with the naming of different elements too, sound movement, for example (ascending – descending), intervals, and so on.

After reading and writing, the area of greatest expression of auditory intelligence is harmony, i.e. the vertical component of music and knowledge of the relationships between chords.

As Carl Eitz, a renowned German pedagogue, used to say, note names are like little hooks that help us memorise sounds. We introduce them very early on in musical education – as early as the 1st level of initiation – as simple names of sounds, onomatopoeia in short. They are first introduced by song lyrics, which contain them, and then the lyrics are sometimes replaced by the names of the sounds. Songs in joint degrees are very useful. From the 3rd degree of initiation we work in a directed way on the association of sounds and the names of notes so that it becomes as perfect and natural as possible, since this makes musical activity much easier. Many of the working principles in the 3rd and, of course, 4th degrees are devoted to this very objective. We sing the names of the notes in the scales, the cycle of the diatonic major scale, various ordinances, songs and improvisations. The activity must be constant and conscious, and the teacher must lead it with patience, because the process is long. Little by little we intensify the demands of the work. All this is done orally, without writing a note. But automation is also helped, of course, by reading with note names and writing (copying, transcribing, transposing, dictating, self-dictating, writing the pupils’ own inventions or compositions).

Latin solmisation compared with the musical alphabet

Willems used Latin solmisation for his pedagogical approach.

The 3rd degree or preparation for solfeggio as Willems imagined it cannot therefore be practised with the use of the musical alphabet. In environments where the musical alphabet is predominant, it is necessary for teachers to find the appropriate path and introduce the musical alphabet into their work at the right time. From personal experience I can say that this is feasible, but that it slows down the process of appropriating the names of notes, just as bilingualism can slow down the acquisition of a mother tongue.

When I obtained my Willems® Pedagogical Diploma and opened my music school in Slovenia, I had to choose how to name the sounds we were going to use.

Because in Slovenia the musical alphabet is predominant, even in singing. In the end, I decided to use solmisation exclusively for musical initiation and to introduce the musical alphabet for the transition to the 4th degree. After that I use both systems in parallel, and at every solfeggio lesson I touch on both. Solmisation is used regularly for singing and we often sing with the alphabet when we read. When we’re dealing with music theory, I use the alphabet exclusively, as it’s more practical and clearer.

I have found that children who over the years learn to master tonal relationships in reading, dictation and improvisation have no difficulty in either system, even though they respond faster and better with solmisation. Children who have difficulty mastering intervals, degrees or other melodic elements have the same problems in both systems.

The solution therefore lies not in one system or the other, but in a thorough understanding of the melodic structures of musical language.

Like note names, degrees are also musical symbols, but they only come into their own a little later (from the 2nd degree onwards), since they are more abstract. Willems warned us not to attach too much importance to degrees at the start of learning solfeggio.

The first association we need to work on is: the sound / the name of the sound.

Harmony

Chords and chord progressions represent the world of harmony, in which aural intelligence finds its strongest expression. Chords certainly have their material basis and their sensible value, but the reality of chords and harmony can only be encompassed by intelligence, since the characteristic element of harmony is simultaneity, synthesis, and this presupposes analysis.

Synthesis and analysis are essentially mental functions.

Intelligence should always be linked to sensoriality and affectivity. If not, we will fall back into theoretical teaching instead of educating the ear and music. From the sensory point of view, a chord is a set of three sounds (minimum 3). From an affective point of view, it is the set of two intervals at least, the relationships between which will be analysed, while from an intellectual point of view it represents a mental function, its most important dimension.

In particular, this function regulates the sequence of chords, and with them the harmony.

High-quality musicians express a fourth dimension: intuition. Intuition can be found in all areas of music, but it finds – like a supra-mental human faculty of synthesis at the highest level – its crucial role in chord sequencing, harmony and composition. Material harmony, represented by the simultaneity of sounds, reaches in art – through intuition – the spiritual level in its entirety, or in the unity of rhythm, melody and harmony.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF SINGING

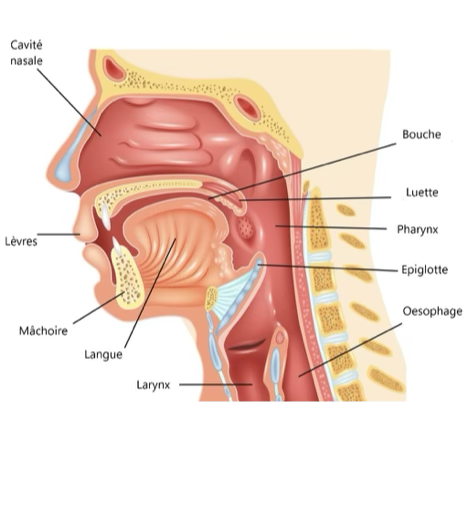

Before talking about singing, we need to explain how the phonatory organ works. Without going into the vast problems of vocal technique in detail, it is important for all music teachers to know at least a little about how the vocal cords work. Here is a brief description.

A simple description of how the vocal cords work

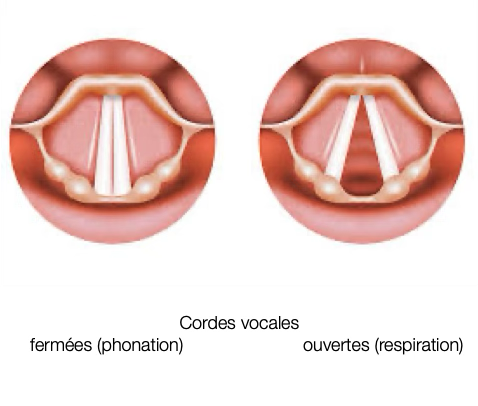

The vocal cords are located in the larynx, at throat level.

They are two flexible bands of muscle, stretched like elastic bands.

During normal breathing, the vocal cords are open to allow air to pass through without sound. To produce sound, the vocal cords are drawn together and tightened. Air from the lungs passes between them, causing them to vibrate.

It is these vibrations that produce the raw sound. The tension, thickness and speed of the vibration modify the pitch (low or high) and timbre of the sound. The mouth, tongue and lips then shape this raw sound into words, precise sounds and, of course, a song!

Video of the vocal cords in action.

The relationship between the ear and the voice

The ear is where we receive and form the information that is translated into sound in our brain. The voice is the most important human expression and at the same time identifies the person, since every human being has a unique voice.

So when we talk about the ear and the voice, we are talking about the reception of sound and expression through sound, the basis of musical language and musical art.

Willems quotes Wagner in the second part of his psychological foundations: “Singing, singing and more singing. Singing is once and for all the language by which man communicates with others in a musical manner… The oldest, truest and most beautiful instrument is the human voice; it is to it that music owes its existence.”

Willems emphasised the importance of developing the ear and the voice in early musical education. It is only when children have learned to listen and express themselves musically through the voice – in music this means above all through singing – that they will really be ready to deal with music theory and the instrument. Through the instrument, children can express themselves in a different way from what they can with their voice. The instrument is an extension of the human voice.

When we work in the field of music education, we want children to develop a natural, warm voice with accurate intonation and precise articulation, through which they can express their inner musical life. Singing involves the whole body. Posture and breathing are important – as you exhale, the voice passes through the vocal cords, mouth and nasal cavity, which are important for articulation and resonance (amplification) of the sound. Every change in space affects the formation of sound – either from the space where the sound meets inside the body or from the space outside. An important element in singing is the diaphragm, the muscle that separates the abdominal part (of the digestive system) from the chest and lungs; it regulates the flow of air. The vocal cords are located in the throat. They are two thin, elastic, mucus-covered folds in a horizontal position. The pitch of the sound produced by the vibrating vocal cords, caused by the passage of air, depends on their length and thickness. When we speak or sing, the vocal cords are taut – this is the result of the work of the muscles that regulate their tension.

The voice plays an important part in all lessons from the 1st level of musical initiation. The first principle of the first part of the lesson is aimed at sensory and emotional auditory development, but – I would add: always in conjunction with vocal development – it is the listening to and production of panchromatic and diatonic sound movement. For a clear presentation and the creation of useful associations, we use instruments, which also show the movement of sound in a visual way – these are above all the slide flute, the xylophone and the carillon. We also use the siren, which has a softer, rounder sound, so the sound movement is no longer visible. The children listen and imitate the sound movements with their voices. It’s important that the child’s attention is always focused on listening to the instrument or the teacher’s voice and their own voice.

The children also invent sound movements, actively explore the pitch of the sound, and by practising all kinds of glissandi, broaden their vocal range. We accompany our singing with the hand, which shows the ascending or descending sound movement in space, giving visual expression to the notions of ascending and descending. In a similar way, we also work in the field of isolated low, medium or high-pitched sounds. Even if the pitch is the most important, during imitations we also direct the child’s attention to duration and timbre. By listening, children recognise the different emitters and elements of the sound they are imitating with their voice, and in this way they also learn to get to know their own voice and how to use it.

By repeating and inventing melodic intervals, we enter into affective auditory development, in which the relationships between sounds are paramount. Here, too, we can use a variety of instruments (such as cuckoo clocks and various calls). When it comes to imitating and inventing melodic motifs, it’s the voice that comes to the fore – both for the teacher and the pupil. Repetition and invention are practised in groups as well as individually, in good proportion to the feeling of safety in the group. Practising as a group makes it possible to perform more confidently and more calmly, while the individual verification of the children is also necessary in order to make progress in the accuracy of individual intonation, to create a beautiful legato and to reveal the beauty of each child’s voice. The child also participates vocally when we use the sound pipes – the combination of the physical force of the muscles that turn the pipe and produce the high-pitched harmonics, and the singing of these harmonics is a valuable experience for the child. In doing so, we establish a link between the energy invested and the pitch of the sound, which is essential in singing.

The voice also plays a part in the second part of the lesson, devoted to developing a sense of rhythm. With the voice, we often amplify the rhythmic beats with our hands on the table or with whole-body movements (jumping, clapping, etc.) – usually using onomatopoeia. Sometimes we can also use words – in which case we create the rhythm of spoken language by clapping our hands on the table, since spoken language is an important source of rhythm. In this way the link between the ear and the rhythmic movement of the body is further stimulated, the voice being an amplification of the sound effect of the body in movement which improves the co-ordination between the ear, the brain and the physical movement.

The voice takes centre stage in the third part of the lesson, devoted to singing songs. Songs are extremely important for the child’s encounter with music, because they represent a complete musical experience in which the child can actively participate as a performer. They link melody, rhythm, harmony and story into a musical unit, making the child feel the connection and interdependence of the different musical elements.

The choice of songs we use when working with children has to be done very carefully and professionally. This is important because the songs represent a strong point, perhaps the most important one, in the impregnation we offer the pupils. They must be appropriate and inspiring both musically and lyrically. We need to be aware that the choice of songs also includes a cultural aspect, as songs reflect our history, language, religion and way of life. That’s why popular songs have a particular meaning. When we use foreign songs to enrich our repertoire, we have to pay attention to the quality of the translation and preserve the authenticity of the song, taking into account the prosody, the concordance between the lyrics, the musical phrase and the rhyme. We also pay attention to all these elements when choosing songs by authors, because not all songs are of the same quality. There are also songs that have a pedagogical value – we use a lot of two- to five-note songs, which have a smaller range and are very appropriate later on for instrumental beginnings; interval and chord songs; songs that are interesting for their rhythmic content and songs that contain the names of notes in the lyrics.

When practising these songs, we pay attention to beautiful phrasing, clear pronunciation, natural breathing, legato and articulation. When we accompany the songs with rhythmic instruments, we must not fall back into syllabification, which we unfortunately often hear in nurseries, kindergartens and schools.

The child can also participate with his or her voice in the natural body movement sequence; for example, he or she can sing the melody of compositions that the teacher suggests several times as a starting point for the movement, or by singing songs that are suitable for this practice. In this way, the child performs the song and the movements, which are coordinated, tuning in to the rhythmic modes, for example: the rhythm when singing, the tempo when walking, the measure, the division or an ostinato in the hands. This is how you establish the connections between the ear, the body in movement and the brain, while from a musical point of view it’s all about combining the different elements into a harmonious, balanced and artistic whole.

In the second dégrée of musical initiation, the child is already accustomed to vocal expression through singing. They can control their voice to a certain extent, can produce different sound movements, imitate different instruments, repeat the pitch of an isolated sound and invent sounds of different pitches. In terms of rhythm, they have acquired the basic relationship between gesture and sound, and know how to direct their physical energy in the production of simple rhythms. They know a lot of songs and feel the regularity or pulse of the music they are listening to, being able to tune their body movements to it. This is why we can continue by gradually adding to the elements acquired the graphics of sound and rhythmic content, the names of notes and other 2nd level content. The introduction of graphics is always accompanied by vocal expression, until we are certain that the child is producing the graphics from inner hearing.

CONCLUSION

Inner hearing, which is so important for all musicians and which I mentioned at the beginning, is the very basis of singing, which is linked to a well-developed musical ear. This is why singing plays such an important role throughout musical education, even when the child, having completed the 3rd stage (preparation for solfeggio and the instrument), begins to study living solfeggio and to learn to play the instrument.

In his works, Willems emphasised the importance of singing, which enables a living contact with music in its entirety. Singing offers children a rich and active musical experience, linked to the rhythm, melody and harmony of the song. Through song, the child, who is largely an emotional being, can encounter different sensations and emotions, individualise them with the help of music and recognise them in themselves and their companions. The voice is therefore an important means of bringing the child into contact with music in all three dimensions – physiological, emotional and mental. It is also a powerful element in the association, awareness and coordination of musical content, knowledge and skills. We must not forget that vocal expression and singing must be linked to a musically heightened (educated) ear – this is the only guarantee of a real musical foundation for the development of a good musician, who will be able to hear music and perform it to a very high standard.

Sources : works by Edgar Willems

With thanks to Christophe Lazerges for his proofreading and translations.