This is the dissertation I wrote for my Willems® Didactic Diploma in 2005.

It presents a synthesis of Edgar Willems’ most voluminous book:

“Le Rythme Musical – Rythme, Rythmique, Métrique” published by Presse Universitaire de France in 1954, reissued by Éditions Pro Musica in 1976 (out of print).

Move your mouse over the yellow headings on the Memoir Outline and click on the highlighted blue heading to go directly to the relevant chapter, and on the arrow at the bottom right to go to the top of the page.

Musical Rhythm

Didactic dissertation by Christophe Lazerges

24-10-2005

DISSERTATION PLAN

MUSICAL RHYTHM – Part 1

Definitions and sources of inspiration for musical rhythm

- The notion of Rhythm

- Rhythm-Melody-Harmony

- Rhythm and the human being

- From sound to musical rhythm: the specific qualities of musical rhythm

- Agogic, dynamic and plastic elements

- Definitions of Rhythm

- The movement

- Time and duration

- Musical time

- The space

- Forms of musical rhythm

Free rhythm – Rhythmic rhythm – Measured rhythm

II – Sources of inspiration for musical rhythm

MUSICAL RHYTHM – Part 2

Rhythm in Music Education

I – Introduction to rhythm – Syncretic life

A – Striking and rhythmic instinct

- Stretching

- Reaction games

- Fast strokes

- Reproducing and inventing rhythmic patterns

- Dynamic nuances

- Agogic nuances: speed – duration

- Striking the rhythms of language

- Graphics

C – Musical rhythm and natural body movements

B – Writing and reading musical rhythm.

A – Physical preparation for playing an instrument

INTRODUCTION

Musical Rhythm:

introduction to the work of Edgar Willems.

Of all the areas of music education tackled by Edgar Willems, rhythm occupies a singular place: unlike “L’oreille musicale”, and above all “La valeur humaine de l’éducation musicale”, for which his personal contribution opened up new perspectives, his contribution to the field of musical rhythm was first and foremost to gather together and synthesise all the writings and practices on the subject, giving his book “The Musical Rhythm” the status of an almost exhaustive scientific reference study in 1976 (87 works cited, 417 authors named). Yet Edgar Willems is not a ‘theorist’ of rhythm. His in-depth study of the sources of rhythm has enabled him to underpin, nourish and invigorate a pedagogical practice, and has given rise to a work that is both dense and pragmatic, enabling today’s educators and musicians to flourish in their daily practice by being more alive and happier, and to spread this joy through their outreach to their pupils and listeners.

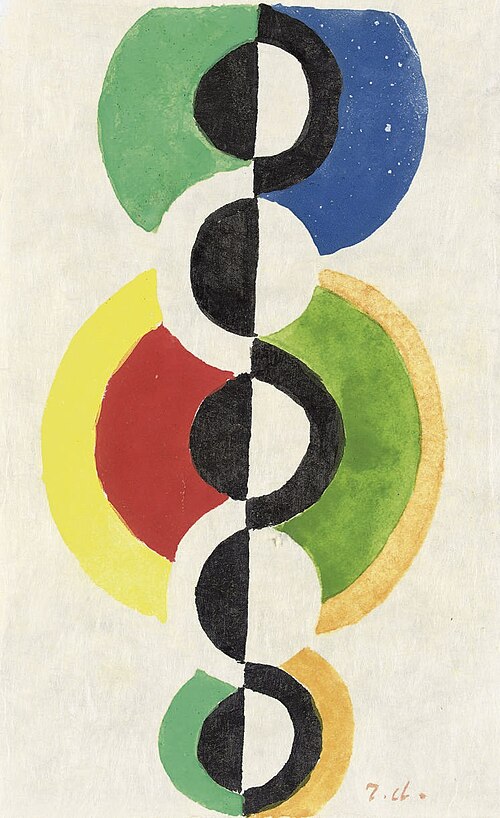

Edgar Willems’ work is marked by the omnipresence of trilogies that reflect and interpenetrate each other. One of the major contributions of this eminent pedagogue is to have clearly related all these trilogies in order to enlighten musicians.

Human nature comprises a physical body, a sensitive heart and an intelligence capable of abstraction and analysis.

Music, for its part, comprises rhythm, melody and harmony.

The relationship between the two is: physical life, for the body and rhythm; emotional life, for the heart and melody; and mental life, for the intelligence and harmony.

In this context, dealing with the theme of musical rhythm cannot be done without constant reference to what surrounds, conditions and penetrates it.

Edgar Willems often presented his ideas in the form of diagrams and tables combining opposing and complementary elements, illustrating the unity of life in its diversity.

Thus essentialism is the opposite and the complement of existentialism, and in the case of musical rhythm, the nature of rhythm, which is living in essence, is distinct from, and even opposed to, the formal elements of music and musical works.

To follow him, we will deal with this subject in two parts:

I – Essentialist: definitions and sources of inspiration for rhythm

II – Existentialist: rhythmic education

Musical Rhythm – Part 1

Definitions and sources of inspiration for musical rhythm

I – Definitions

A – Nature of the Rhythm

We will distinguish three essentially different categories.

Rhythm, which is an actualised vital propulsion, informing a plastic or sound material. Rhythmics, which is the science of rhythmic forms, including writing and the rules of phrasing.

Metric, which is simply a means of measurement.

1. The notion of Rhythm

The word “rhythm” comes from the Greek “rhuthmos“, whose root is “rheô“, meaning “I flow“. It therefore originally related to movement.

Movement is dependent on both life and matter, because it is the forces of life that propel matter. This propulsion is, so to speak, the determining expression of life, in the image of the original Big Bang. It is a universal archetype of a cosmic nature, as present and unexplained as the origin of life.

This propulsion of the vital force is found in all the kingdoms of nature: the movement of atoms in the mineral kingdom, augmented by the movement of cells and sap in the plant kingdom, augmented by the movement of displacement in the animal kingdom, augmented finally (?) by the movement of thought in the human kingdom.

As a function of both Life and Matter, rhythm is difficult to determine. It must therefore be constantly considered in its threefold reality: the living element (artistic), the theory (the means of becoming aware of it), and consciousness itself.

2. Rhythm, Melody, Harmony

Starting from the two extreme poles, one material and the other spiritual, which are the sound material (sound and instrument) on the one hand and the musical spirit (inspiration and art) on the other, Rhythm, Melody and Harmony are the fundamental elements of music. These three elements interpenetrate and influence each other and, by complementing each other, form a harmonious synthesis blending three facts in different proportions, like the thickness of the lines in the following diagram.

3. Rhythm and the human being

Human musical synthesis alone can provide us with the keys to a psychology of music capable of illuminating the living reality of the art of music and the living sources of each of its elements, as the following diagram shows.

It is through physiological life that rhythm makes its characteristic contribution to music.

Nevertheless, musical rhythm is one of the main elements in the expression of feelings. Although movement is not of an emotional nature, it is nevertheless through movements or changes in physiognomy that human beings express joy, sorrow or any other feeling. Rhythm, which is very physical in its mode of expression, is imprinted with emotion. In this way, emotion, by creating beautiful movement, enriches art.

This is why we can speak of an affective rhythm.

Finally, as soon as there is simultaneity, there is mental conception. Polyrhythm is therefore the privileged domain of mental rhythm.

4. From sound to musical rhythm: the specific qualities of musical rhythm

Genetic pathway from non-rhythmic sound to rhythmic sound and then to musical rhythm:

- Continuous sound.

- Sound with irregular interruption.

- Sound with regular interruption.

- Sound with a meaningful variation in duration.

- Sound held with intensity variation.

- Held sound with timbre variation.

- Combinations of rhythms 4. 5. and 6…

The rhythm becomes musical from 7 onwards, combining variations in duration, intensity and timbre. But its realisation begins with a shock of sound.

For analysis, the numerical aspect – the number of shocks – is the most obvious and basic. Then there are duration, intensity and plasticity, i.e. agogic, dynamic and corporeal nuances (on which timbre depends).

5. Agogic, dynamic and plastic elements

Agogic elements have to do with duration and time. For a long time, these were the only elements taken into account for rhythmic awareness, but this is only the mental aspect of the problem: numerical calculation of syllables (then of shocks), then differentiation of syllables into short and long of relative value, finally absolute evaluation of values according to a prime time which allowed proportional writing (born around the twelfth century in the West). Tempo is an agogic element, since it is determined by the length of time between beats. It was only towards the end of the sixteenth century that tempi were designated by the terms “Andante”, “Allegro”, “Adagio”, etc., indicating that they convey a sense of duration that is experienced rather than abstract. If the quantitative takes precedence, only the qualitative gives access to art, because it expresses states of mind.

It was around the same period (16th c.) that indications of intensity were introduced, allowing an affective awareness of rhythm: p – f – pp – ff …

Dynamic elements (from the Greek “dunamis” meaning “force”) can be classified into three categories:

a – general intensity (soft, medium, strong)

b – dynamic nuances (crescendo, decrescendo)

c – various accents (metrical, rhythmic, pathetic, etc.)

Inseparable from duration, intensity expresses emotions and passions.

The plastic element of rhythm has long been neglected, and there are few formulas and special signs in writing to take it into account and awaken physiological awareness of rhythm: . – > – ^ – …

The emission of sound and its articulation (legato, staccato and their derivatives) are elements conducive to plasticity.

Plasticity evokes the material attributes of physical bodies: weight, volume, density, elasticity, etc. Timbre is thus linked to the plastic nature of rhythm, and thus helps to awaken a physiological awareness.

6. Definitions of Rhythm

Edgar Willems quotes Pascal: “Definitions are made only to distinguish the things we name and not to show their nature”.

Two notions vie for first place in the history of definitions of rhythm: movement and order.

The majority of definitions revolve around the notion of movement.

The artist knows that he is transmitting to his work a part of his own life, which he expresses through movement.

Drawing is particularly governed by movement. In the visual arts, movement is frozen, fixed in space, but virtually alive. On the other hand, even spatial proportions take on a value in time through the length of time it takes the eye to traverse them. In reality, space is more closely linked to time than it first appears.

Duality of movement and order

In this duality, movement represents vital propulsion and free rhythm, close to nature and the human organism; order, prescription or organisation represent the limitation that channels life. The two opposing poles can be represented symmetrically, with the extremes equidistant from a centre representing the ideal rhythm, the most rhythmic, neither too free nor too regular, combining strength and grace, rigidity and suppleness.

After movement, it is the principle of order, proportion and organisation that wins the most votes.

Platon’s definition: “Rhythm is the order of movement”.

Definition by Aristoxenus: “Rhythm is order in the distribution of durations”.

Definition by V. d’Indy: “Order and proportion in space and time is the definition of rhythm”.

Definition by W. Howard: “Rhythm in the original and beautiful sense is the ordering of time.

For Edgar Willems: “Rhythm, which is both a spiritual need and a material necessity within and without man, is the first of the three fundamental elements of music. Without rhythm there is neither melody nor harmony. It exists outside music, where, as in the other arts and in the phenomena of nature, it represents the first manifestation of life.

He links the two notions in this formula: “Life creates rhythm by creating movement and organising it”. He then inserted the concept of relativity, essential to art, between these two concepts. This leads him to the following definition:

“Rhythm is a relativity between movement and order”.

It is the relative value of the notions of movement and order that makes artistic uniqueness possible.

“Every work of art, every rhythm, has its primary value in that which makes it homogeneous: beauty. It is beauty that must govern the reciprocal relationships of the various elements”.

And echoing the thought of Saint Augustine: “Rhythm is a beautiful movement”.

B – Movement – Time – Space

1. The movement

The raison d’être, the profound nature of movement, eludes us. Edgar Willems cites the various philosophical currents that have attempted to define movement. He seems to agree with Raoul Piquet, a physicist from Geneva, who wrote in 1896: “the mind is a primary cause of the movement of matter … the definition of mind in experimental physics is any cause of spontaneous movement of matter, without any possible mechanical explanation”. Here we find a constant in Willems’ work: distinguishing the nature of the elements under consideration by permeable boundaries. Thus, movement is defined as the mobility of matter, but the source of mobility is immaterial, spiritual! The force of the spirit, which is found in thought and imagination (motor, for rhythm), is of prime importance to the educator.

“Through movement, we become aware of space and time, and therefore of the most diverse rhythms. In music, the motor imagination will often take the place of real movement, creating – as in the creation or reading of works – an indissoluble link between matter and spirit”.

“In musical practice, bodily movement in general (breathing, walking, etc.) enlivens the rhythm, not necessarily directly, but indirectly by encouraging the circulation of blood which, by the physiological balance it creates and the vitality it increases, stimulates the general rhythmic expression”.

But “the spiritual vigour of rhythm depends on our attitude to life”.

2. Time and duration

Music is the art of time, because of its rhythm. But it is impossible to be aware of time as such. It is only through duration that we can grasp an aspect of time. And this duration, which can be evaluated by the clock and expressed by mathematical values, can be experienced more immediately, both instinctively and consciously, through bodily movements. To quote Saint Augustine: “The world was born at the same time as time, since movement was created with the world”.

Time is a function of movement; it flows unperturbed; it is irreversible. E. Willems distinguishes four types of time:

a) Physical time: astronomical, mathematical, quantitative and measurable, chronometric. It is “hourly” time.

b) Physiological time involves active participation in the passage of time. Conscious or unconscious participation.

c) Affective time: the influence of human beings’ emotional states on their awareness of the passage of time: impatience lengthens it, happiness tends to shorten it, sometimes even to abolish it. It is artistic time par excellence. It embodies the ideal of beauty, sensitive to the laws of the soul and the body.

d) Mental time: intellectual, abstract. Mainly concerns the proportions of a work, in its construction and architecture. It is based on physical time but differs from it in that it can be conceived in a single instant. Through the motor imagination, based on physiological experience, it can be linked to the sensation of the passage of time.

3. Musical time

Willems contrasts “hourly” time with “ontological” time, which brings together physiological, affective and mental time through what unites them: psychic, lived time, as opposed to chronometric time. In this ontological time, the composer, the performer, the reader or the listener are active musically speaking. It is a complex, variable time, rich in all human materiality and spirituality. It has a lived sense of proportionality, speed and duration.

This musical time is therefore an ensemble of various human times experienced in music.

4. The space

Space is more material than time, which is itself more spiritual. But awareness of the passage of time can, in principle, only come to us through a kind of transposition into space, through a bodily movement or by imagining the time necessary for its realisation.

Sound, a vibratory frequency, takes place in time; intensity, on the other hand, which depends on the amplitude of the vibration, unfolds in space. The stronger the rhythmic intensity, the more space is required to achieve it.

Through the proportions of its sound values, rhythm is temporal, through its intensity it is spatial and through its plasticity it becomes material.

5. Forms of musical rhythm

Free rhythm – Rhythmic rhythm – Measured rhythm

- Rhythm is ordered movement.

- Rhythm is the ordering of movement.

- Metric is the measure of movement.

Rhythm is said to be free when it cannot be fixed in any form, subjected to any unit, identifiable primary time. It is the rhythm that is always unexpected, the result of a propulsion whose impulse is as profound as it is unpredictable. It is the rhythm of the explosions of an erupting volcano, of thunder and the echo of its roar, of the explosions of firework rockets… So many examples to imitate, seeking to reproduce the contrasts, the silences of expectation, the unpredictability of explosions through sound shocks.

Rhythm becomes rhythmic as soon as a regular pulse, or tempo, emerges from it, without, however, being able to measure regular periods, marked by a strong beat, for example. We can draw inspiration from the songs of birds such as the sparrow, whose ‘chirp-chirp’ is both regular and unpredictable; or the almost uninterrupted barking of an isolated, shut-in dog; or the ebb and flow of the waves of the sea, in some cases when it is calm, or the little fluttery cries of toads, etc. ….

From being rhythmic, rhythm becomes metrical if it can be measured, grouping several beats or pulses into a period. Since measurement can only be carried out by the intellect, there is a great risk of losing the dynamic and above all plastic qualities of rhythm, to the sole benefit of agogic values, whose proportions of duration are themselves easily quantifiable.

That’s why it’s also important to continue to experience the measured rhythm physically, through movement in space.

II – Sources of inspiration for musical rhythm

Art only begins with the awakening of artistic awareness, with the need to express beauty. The sources from which art draws, on the other hand, have existed from time immemorial: they are in man and in nature. True art is always close to life, and differs from it only in its desire to create beauty.

Music has always been linked to at least two important sources, dance and the spoken word, but musicians are influenced by many other things, more or less consciously.

A – Noise

1. The sounds of nature

Contemplating the manifestations of nature has an ennobling effect on the soul.

Some sounds are more rhythmic, like thunder and the waves of the sea. Others are more melodic, like wind, rain and fire. Rhythmic and melodic lines often merge, and their allure touches the whole being.

2. Noise from machines and looms

It’s more a question of metre than rhythm. But regular rhythm can have incantatory effects that can border on obsession and bewitchment. For example, the pendular rhythm of the clock, the ticking of the mill, the locomotive, the spinning wheel and the more complicated and varied rhythms of the trades: blacksmiths, sawyers, lumberjacks, oarsmen, sailors… Many songs have been created, carried by the rhythm of a particular job, by the repetition of a gesture, of a movement.

B – Movements

1. Non-sonic plant movements

Since movement is the source of rhythm, observing the movements of plants, which are not sonorous because of their slowness, can influence the musician’s subconscious: rigidity or suppleness, expansion or contraction, the rise and fall of branches; tendrils and other twists.

2. Animal movements

The cries of insects and animals, their movements and paces, have always inspired the musician: the gallop of the horse, the march of the elephant, the waddle of the duck, the hopping and flying of birds, the flight of butterflies, insects… All these movements, with their pure, unadulterated rhythm, appeal to the imagination and engage our bodily dynamism.

3. Human movement – dance

The creative instinct is influenced by the heartbeat, breathing and walking. But the regularity of these movements, which are often pendular, is not metrical, because they are always imbued with a temperament that they reveal. Here are a few extracts from the rich and varied range of human movements: play (running, jumping, swaying, rising, falling, attacking…), love (caressing, desire, movement of the hips…), worship and magic, work (hunting, fishing, cultivation, clothing…), housing, boats, war…

Dance and music have always been linked by the profound nature of rhythm: its physicality. But true dance is pure plasticity. It can exist on its own, without music. With the addition of music, it is enhanced by everything that can penetrate the human soul through the ear. And yet, if dance is the joy of movement and music is the joy of song, then the two arts have emotion rather than dynamism as their common source. The body in dance and the rhythm in music would both be the necessary medium for emotional expression.

C – Languages

1. Birdsong

Birdsong has an infinite variety of rhythms and melodies. They are often very difficult to isolate and even more difficult to transcribe. Nevertheless, they have been a source of inspiration for the greatest composers, whether this influence was conscious or unconscious. Translating birdsong into phrases and interjections can be a way of making it our own and feeding our subconscious with the rhythmic fantasy of these “servants of immaterial joy”, as Olivier Messiaen put it.

2. Language and poetry

Music is a language. Like spoken language, it originates in a need for expression and communication, using sound and rhythm. Prose and prosody have a free rhythm, while psalmody has a more incantatory rhythm. Poetry is a musicalised language, because it gives more importance to rhythm and sound than everyday language.

D – Music

1. Traditions

Throughout the ages, the musical creation of the masters has been enriched by popular song, whose rhythm often reflects a spontaneity unbroken by rules and conventions.

In more than one country, composers have drawn inspiration from folklore to create national music. Like Greek music, plainchant is characterised by a free, unmeasured rhythm.

This makes it a powerful counterweight to metricism and musical materialism. In this case, it has had a decisive influence on modern music.

Exotic music is also an inexhaustible source of models and rhythmic life.

2. Examples from Masters

Traditional teaching is based on the cult and imitation of the masters’ masterpieces: themselves nourished by tradition, enriched by contact with impersonal musical examples such as popular song, plainsong and exotic music, they show us in their works possible paths, life to be revealed and recreated.

3. Musical instruments

Does music come from instruments?

To a certain extent, its external material form depends on it, but not its spiritual essence, which comes from a need for expression in the realm of beauty. So it is not the instrument that is at the origin of music. But just as human life depends on matter, the material nature of instruments has an influence on music, and instruments can also be seen as sources of inspiration for musicians.

Musical Rhythm – Part 2

Rhythm in Music Education

If musical education is to remain as lively as possible, it must start from musical life itself as the subject of analysis and awareness, and thus make it possible to revitalise musical practice of the works of the past while leaving open the doors to invention and present and future musical creation. Starting from the whole and returning to the whole is the subject of this second part, which will deal successively with musical initiation, then with music theory and finally with the instrument.

I – Introduction to rhythm – Syncretic life

In an introductory music lesson, rhythmic development is the second part, after auditory and vocal development, and before songs and natural body movements. Starting with the overall, syncretic rhythmic life (unconscious synthesis), expressed by stretching and then sound shocks, we then go on to detail all the qualities of rhythm in isolation.

A – Striking and rhythmic instinct

The first thing to do with the students is to reveal and trigger their rhythmic life through the example given by the teacher. The teacher must constantly bear in mind that rhythm is movement, movement that provokes a sound through a shock, movement that always comprises three phases (momentum, shock and rebound), movement that is ordered in a given context and that must serve beauty. Beauty of gesture, of plasticity, of the quality of the attention paid to the whole, beauty of the motif, determined not by the motif itself, but by the quality of the presence of the person creating it.

1. Stretching

A source of relaxation, they are both a transition following the less dynamic auditory and vocal development, and an introduction to plastic rhythm. They can be accompanied by vocables or onomatopoeia. Practised preferably standing, using mainly the arms and hands, but also the legs and feet, they stimulate blood circulation throughout the body and contribute to better oxygenation of the brain.

The mind is then sharper and more receptive to new rhythmic stimuli (among other things). These movements can also be practised while listening to great works, preferably symphonic ones, for a broader immersion in the timbres.

2. Reaction games

Designed to arouse the attention and interest of the pupils, and solicit their physical dynamism, these consist of rapid clapping by the whole group, stopping instantly at a given signal: “Hop – Stop”! Preferably alternating hands on a table, failing that on the knees or with the feet.

3. Fast strokes

A more or less regular succession of shocks is the first rational perception of a rhythmic motif. That’s why the real thing comes just after the senses are awakened. Listening to, reproducing and inventing a series of rapid taps maintains interest, feeds and develops memory and precision, and stimulates the imagination. The sound hammer is the king of instruments in the sequence, but a tambourine, a timpani, a wood-block, sticks, or simply hands on the table can do the trick.

4. Reproducing and inventing rhythmic patterns

Different types of rhythm can be presented: free, rhythmic or metrical.

The importance of the living example cannot be over-emphasised, nor can the various qualities of the rhythm to be used: speed, intensity, duration and plasticity!

It’s the diversity and blending of contrasts of all these elements that ensures the piece stays alive. Reproducing a motif immediately establishes a structure. It doesn’t have to be systematic, but it’s the only way to educate and learn. In the words of poet Jacques Prévert, “Répétez! dit le maître” (repeat! says the teacher) helps you perfect a gesture, synchronise your strokes with your voice, specify a number of shocks and fix images in your memory.

5. Dynamic nuances

Intensity is the most emotional quality of rhythm. What child, in front of a drum, can resist the desire to make as much noise as possible? And what group of children can resist bursting into laughter when one of them hits the cymbal held out to them as hard as possible? It’s only natural, because “dynamic” comes from the Greek “Dunamis”, which means strength. Showing off your strength is a way of proving that you exist!

Dynamism is a source of joy, and while it is important to channel it, it must not be stifled! Noise is often a sign of disorder and is therefore feared by many teachers. Channelling a child’s desire for noise in a music class is as important for the classroom environment as mastering a child’s means of expression. It’s one thing to enjoy making noise (and defying a ban), and quite another to be able to play with the contrasts between loud and soft at will. When playing loudly is authorised and encouraged, then the challenge is no longer to defy the prohibition and the exploration of dynamic nuances is possible.

As always, use contrasts, contrasting loud and softer motifs, playing with crescendo and decrescendo and distinguishing between intensity and speed. Accents marking a series of regular strokes prepare the way for metrical accents, but when placed non-periodically, they help to anchor the child’s sense of tempo by opening the door to so-called rhythmic, unmeasured rhythm.

6. Agogic nuances: speed – duration

a) Although tempo is agogic in nature, since it concerns the duration between each impulse, what characterises it is not duration but speed. Speed and duration are linked to the passage of time, but speed conveys the state of mind in which durations evolve.

In the absence of long sounds, a close succession of short sounds will resemble a fast tempo. Conversely, if the short tones are separated by silences, they can determine a slow tempo.

Tempo reflects the inner state in which we move through time: joyful, agitated (allegro, agitato), serene, jovial, preoccupied (andante), sad, sombre, meditative (adagio), etc. Body movements to the music, and in particular walking, will help you to become aware of this.

b) A concept can always be defined and understood by opposing it to its opposite. In the sequence of rhythmic strokes, this is easily assimilated by games contrasting speed and slowness, but also by the progression from one to the other: accelerando and rallentando. The associated moods can also be opposed: joy and sadness, lightness and heaviness, parrying and fleeing, etc.

The different gaits of the horse and the movements of other animals can also be used to illustrate the subject and stimulate the imagination.

c) Along with the numbering of shocks (tackled with the fast strokes), the different values of duration are the visible face of the “Rhythm” iceberg, because when they are proportioned, they allow rhythmic writing, based on the ratio of single to double.

d) Distinguishing between speed and duration is often difficult, especially for adults. Particular care must therefore be taken with presentation.

During the auditory development sequence with the bells, emphasise the differences in duration of the resonances. This is when there is no idea of speed.

During the striking sequence, play with long or short sounds associated with an invisible thread pulled in front of you between your two hands. Once the principle has been taken out of any instrumental context involving timbre, intensity and pitch, it will be easy to assimilate. You can then use crotales, triangles, cymbals, etc. without fear of confusing associations.

7. Striking the rhythms of language

Striking each syllable spoken with the hand or fingers on the table, ensuring the greatest possible synchronisation, highlights the rhythmic qualities of the language while giving the rhythm the appearance of language and encouraging rhythmic invention by avoiding stereotypes. Dynamics and variations in speed must not be neglected. Here again, the teacher’s example is crucial to avoid turning the exercise into a sterile caricature.

8. Graphics

Characteristic of the 2nd level of musical initiation in the Willems progression, they allow both an awareness of the elements concerned in their diversity, and a preparation for reading and writing music through signs that are directly meaningful to the child because they naturally extend the practice of the 1st level.

There are three rhythm-related symbols:

– for rapid vertical strokes │││ │││ ││ ││││ which prefigure the tails of musical notes.

– for STRONG and softer colours, thicker or darker vertical lines ││▐▐ ││▐ or larger or smallerı ı ı ı│ foreshadowing the < and > signs.

– for short and long, short or long horizontal lines – – —— signifying, by the length of the line, the space covered during the time that the sound lasted.

These graphics come into play at a time in the child’s musical initiation when the dynamic and agogic possibilities can be developed further.

In addition to the loud/soft contrast, the notion of regularity will be added to reinforce the sense of tempo and accents:

▐ │▐ │▐ │ … ▐ ││▐ ││▐ ││ … ▐ │││▐ │││▐ │││ … opposed to ││▐ ▐ ││▐ ││ ││▐ ││▐ ▐ ▐ … where the accents are not periodic.

The short/long contrast will be joined by the notion of proportion:

1 for 2 : – – —– – – —– – – —– – – —–

1 for 3 : – – – —–– – – – —–– – – – —–– – – – —––

1 for 4 : – – – – —––––– – – – – —–––––– – – – —– – – – – —–––––

Opposed to – – – – —–—— – – – – – — —–———–—— – – – – ——–—— free.

Silence is represented by blank spaces.

At 3rd level, the rhythmic values of quarter notes and half notes are written in the ratio of 1 to 2, followed by all the others throughout the solfeggio.

B – Rhythm and songs

With songs, the introductory music lesson rediscovers the totality of music, since they are a synthesis of rhythm (for which the text is the driving force), melody and harmony (either suggested by the melody or realised by an accompanying instrument).

1. The four rhythmic modes

- Rhythm: this corresponds to all the notes in the musical text, and therefore to the duration relationships associated with syllable or sound clashes. Rhythm is generally made up of a varied combination of short and long sounds, not regular but proportionate. In a song, it is identified with the lyrics.

- Tempo: a regular element that reveals the speed and character of the song. When singing while walking, the regular clash of steps expresses the tempo.

- The 1st beat of the bar: derived from the tempo, the upbeat marks the longer periods that structure the discourse, from 1 to 5 or even 6 or 7 beats. The image of the most common periods (2 to 4) is given by human breathing. The tempo determines the duration of an inhalation beat, with exhalation taking place on the other beats. The 1st beat of exhalation determines the 1st beat of the bar.

- Time division: binary or ternary, it reflects the heartbeat (ternary at rest, binary during effort). To determine this, you need to strike the tempo then divide it into two (tick-tock, tick-tock…) or three (tick-tock-tock; tick-tock-tock…) and choose the one that most naturally corresponds to the music in question.

2. The strikes associated with the songs

Songs have the great advantage of being generally short, expressive and varied from one to the next. This makes them a valuable teaching tool for intonation, interval awareness and recognition, and rhythm. But the song should only be used once it has been assimilated, i.e. memorised with the words, without the words and transposed into a vocalise.

The lyrics can then be sung by striking the rhythm, then the tempo (1st degree), then the 1st beat of the bar and the division of the tempo (2nd degree). As soon as the four rhythmic modes are distinctly performed, two, three and then four modes can be combined simultaneously in as many groups.

In the 3rd degree, pre-sologetic and pre-instrumental, individual polyrhythm will gradually be introduced, first of all according to the three levels of the body: the feet for the market beat, the head for the sung rhythm (with lyrics) and the hands for one of the four rhythmic modes (starting with the rhythm or tempo, reinforcing the head or legs, then the 1st beat and finally the division). The next step in individual polyrhythm is to combine two elements at the same level: one in each hand, then the feet…

Rhythm + (Tempo or Measure or Division) and so on up to four-part polyrhythm: 1 mode per member! You can even strike a rhythmic ostinato in place of the rhythm, which remains sung… making five simultaneous elements! But these feats are more the subject of music theory and the instrument.

C – Musical rhythm and natural body movements

Since movement is the only way to become aware of the passage of time, all aspects of rhythm were embodied in the second part of the introductory music lesson through gestures and concrete, lively, plastic rhythmic tapping.

Combined with songs, rhythmic tapping remains a secondary pedagogical application, compared with singing itself, the carrier of the melody, the heart and centre of the music. Let’s quote Edgar Willems’ apt phrase on this subject:

“In music, rhythm has priority, but melody retains primacy”.

Moving to music and experiencing the contrasts of different atmospheres as a whole is a pleasurable way of feeding the memory of high-motor images that the instrumentalist will later reactivate in his fine motor skills.

These basic and necessary movements are: walking, running, hopping, jumping on the spot, swinging and turning (with the arms). These six movements reflect the child’s life and represent archetypes that are of course found in music. Each of these movements can be played at very different tempi and in very different ways, so that so many different moods can be tamed and expressed.

They are all the more important as children in the 21st century have less developed motor skills than in the past. It is not uncommon for a child not to be able to hop, even though this is a spontaneous movement of joy and carefreeness (a sign of the times?).

These movements are also designed to develop an overall sense of tempo by synchronising the impact of the feet with the musical tempo. This audio-motor listening will be encouraged by the sound and music of the steps of the child invited to move alone.

In the second level, the beats of marching music will also be counted, but not systematically in order to preserve the priority given to atmosphere. Bar beats will be introduced on the basis of the pendular movement of the two-beat bar.

In the third level, you will learn to beat all the bars on the spot and then gradually while walking. Edgar Willems composed numerous piano pieces to illustrate these moments of movement. They are collected in his teaching notebooks n° IX and X.

II – Living solfeggio

Between syncretic life and conscious synthesis, there is the time for analysis by means of theory. This is the meaning of solfeggio. This is the time for systematically learning to read and write in order to acquire the automatisms that allow abstract signs to be brought to life without being hindered by theory. It is also the time to acquire the analytical tools needed to understand and interpret music from all periods and styles. Finally, it’s a chance to step back from a piece of music and broaden your visual field to better understand and serve it, especially for the instrumentalist.

A – Metrics

E. Jaques Dalcroze, quoted by E. Willems, said: “rhythm is a vital principle, measurement an intellectual principle”; and “metric, created by the intellect, mechanically regulates the succession and order of vital elements and their combinations, while rhythm ensures the integrity of the essential principles of life. Metre is a matter of reflection and rhythm is a matter of intuition”.

Metrics should be seen as a special case of rhythmics, itself a special case of rhythm as a vital impulse.

1. Measurement

It has its origins in a natural human tendency to become intellectually aware of musical elements that unfold in time.

There are three main elements to meter:

- Tempo, the essential rhythmic element that expresses the mood of the piece. It is determined by the choice of a primary beat, the duration of which becomes the “unit of time”.

- The bar, the higher unit, determined by the grouping of a certain number of beats. The first beat is often (but not always) a strong beat. This first beat has given rise to the bar line, which is characteristic of Western metrics.

- The subdivision of the beats, giving a unit smaller than the tempo: the pulse. This division is binary or ternary.

2. The measurement beat

Willems warns: “Above all, the teaching of metres should be based on rhythm, i.e. on the sense of bodily movement, which makes it possible to become aware of the passage of time”. But beating time is often the last line of body movement in a music theory lesson. Beating time serves two purposes: firstly, it shows the passage of time through the continuous movement of the arm. This is more physiological and rhythmic than metrical. Secondly, it allows us to become aware of the organisation of rhythm in time through calculation. This is why, in addition to the supple gesture of the beat, you need to count the beats out loud, which provides the clarity needed for reading and dictating music, especially for beginners. It is also essential to practice rhythmic improvisation by beating the beat in order to acquire an awareness of time.

B – Writing and reading musical rhythm.

There is always a twofold difficulty: that of channelling the rhythm into rigid formulas, and the even more delicate problem of restoring to the written formula the life for which it is responsible. Here calculation is powerless and must give way to the driving imagination and artistic sensitivity.

1. Writing musical rhythm

Writing music in general poses different problems from writing language, because it cannot be based on any agreed meaning. A different intonation, a shifted accent and the whole thing takes on a different meaning. Transcribing sounds is therefore more risky than transcribing phonemes. However, the history of writing reminds us that it was originally intended to preserve the memory of texts that had previously been transmitted orally. The first written form was a kind of memory aid. It slowly and progressively became more complex, serving as closely as possible to reproduce the spoken word.

As far as melody was concerned, the problem was relatively simple, since it was simply a matter of indicating relative pitches, and writing was gradually based on the diatonic system. But rhythm consists mainly of three simultaneous elements that cannot be reduced to a single sign: duration, intensity and plasticity. Each of these elements echoes the following different human qualities: mental for duration (quantifiable), affective for intensity, and physical for plasticity.

As writing is the exclusive domain of the intellect, duration has been given priority, leaving the dynamics of the accompanying annotations (p / f / < / >) to the performer’s free judgement.

The learning of rhythm writing, begun in the second level of musical initiation with the three graphs already presented, continued in the third level with the introduction of the values of the black and white notes in the proportions of simple to double as well as the silence of the quarter note, the sigh, is continued in the solfeggio course with the introduction of the bar and all its developments.

Calculation then takes on a more important role, not in the realisation of the rhythm, but in the organisation of the writing. So we begin by placing the barlines in a written rhythmic phrase, indicating the corresponding beat numbers with numbers under the note values, choosing combinations of values likely to ‘fill’ a given bar quantitatively, starting with quarter notes and half notes and the corresponding rests, then rounds… The development of writing should naturally follow that of reading, from which it is inseparable. It is important not to neglect the fairly long time it takes for a child to assimilate signs and the essential practical training required for graphism itself, and to be wary of the fact that a child who understands the abstraction of a phenomenon believes he has assimilated it, when he has not yet experienced it sufficiently physically. Copying from models is very formative, and the quality of the handwriting (legibility, proportion) should be ensured through explained corrections, so that from the outset it remains a pleasure and not a chore.

2. Reading the musical rhythm

As an immediate consequence of writing, reading, which is also begun during the second and third levels of initiation, can and must always have a musical meaning. Although it is necessary to start with the simple values of quarter notes and half notes, and to distinguish them from the values of intensity, speed and plasticity, it is possible to associate everything very quickly with pupils who have been well prepared by the Willems musical initiation.

It is then natural for the child to experience rhythm through movement and dynamics.

The same rhythmic phrase can be played successively in several lively ways: with crescendos or decrescendos, with accents, played on an instrument (timpani, cymbals). Reading a well-proportioned writing of duration values will enable the child to assimilate the fact that the “empty” spaces separating the notes symbolise “full” unfolding time. This is a greater abstraction than the pitch of the notes on a staff, because it renders invisible what the bodily movement had described in space and what the ‘long’ and ‘short’ graphics had conveyed on paper. This is why it is so important to combine the two signs – — before black and white for as long as necessary, and to return to them frequently.

The most common error in rhythm reading is the confusion between the notion of duration and that of speed. But the problem generally arises when eighth-note values are introduced. Until then, the quarter note was the only unit of time taken into account, and the eighth note is the first symbol of time division. However, it is much easier to go from a single note to double its value (the principle of addition and multiplication) than from a single note to half its value (the principle of subtraction and division).

Three concomitant procedures will solve the problem:

- Practising rhythmic modes that are struck in conjunction with simple readings: say a rhythmic phrase by striking the tempo, then the 1st beat, then the binary division, even if it is not written down. Then strike the rhythm with one hand and one of the three regular rhythmic modes with the other.

- With a pattern or rhythmic phrase of exclusive quarter notes and half notes written (on the board), underline it with the corresponding ‘short’ and ‘long’ graphics, then above, establish that the half note can be chosen as the ‘short’ sound reference, which imposes the round note as the ‘long’ sound value. Then, below, establish that the quarter note can be chosen as the ‘long’ sound reference. This imposes a new value for the ‘short’ sound: the eighth note. This ‘coinage’, which is practised regularly, lends credence to the idea that note values represent proportions of duration whose unit of time – the short tone – can change graphically, and not relationships of speed.

- Read the same rhythmic phrase at different speeds, starting from moderate, then faster, and finally and above all, slower – even very slow. Three diction modes will be used: “short-long”; “black’-blanch'” and an onomatopoeia “ta-taa”; “pam-paam”…

3. Progression

Since writing and reading are intellectual, mental and analytical, they must be introduced by the simplest elements, with the overall practice of music having a comfortable head start (rhythmic life, improvisation, rhythmic modes, polyrhythm, body movements, etc.). It is often difficult to maintain organic links between this rich, complex, active and rewarding global life and the relative poverty of the black and white values of early writing and reading. Writing the rhythm of a song that has been well assimilated (“A Paris”; “Dans le bois”, “Hé-hé, j’ai cassé”, “Do-ré-mi, la perdrix”…), seeing it written, recognising it from its written rhythm alone, all of this gives more meaning to writing.

On the other hand, children are not fooled: when they are confronted with the task of writing and reading, they realise very well that it is difficult and do not feel dishonoured by the simplicity of the values. On the other hand, it is vital that they succeed, otherwise they will be afraid of the written word for a long time.

Here’s the order in which the note values are introduced:

- Third degree: black, white and sigh.

- In 1st year solfeggio: round, pause, half-pause, two tied minims, tied minim to quarter note and dotted minim, then two eighth notes and four sixteenth notes. Measures in 2/4, 3/4 and 4/4 without cyphering.

- In 2nd year solfeggio: eighth note/half note, quarter note tied to eighth note then dotted quarter note, half note/eighth note.

Ciphering of bars in 2/4, 3/4, 4/4 and 5/4. - In 3rd year: eighth note/two sixteenth notes, two sixteenth notes/eighth note, dotted eighth note/double note, dotted sixteenth note/double note, triplet of eighth notes.

Measures in 3/8 and 6/8. - In 4th year: off-beats and syncopations corresponding to known values, eighth/fourteenth notes, eighth/two-two notes/eighth note, and their simple derivatives.

Measures 9/8 and 12/8. - In 5th year: all binary and ternary combinations up to sixteenth notes.

Finally, it should not be forgotten that rhythmic reading is the driving force behind melodic reading. It must therefore always be ahead of melodic reading, so as to draw the eye forward and bring with it the consideration of the pitches of the notes. This is why rhythmic reading is separated from melodic reading.

C- Memory – Dictation

1. The memory

Memory comprises two stages: the retention of images in the nervous system, and the retrieval of these images on command by the brain.

Memory is selective. It is now accepted that all images sent to the brain by our senses can potentially be retained, but the depth of the imprint they leave depends on the degree of affectivity associated with the image itself. The greater the affect, the deeper the imprint. Restitution will also be proportional.

It is therefore important to encourage memorisation with the support and enjoyment of the child, through active participation and the body as a whole, so that the written signs can reactivate the life that the imprint will have left.

For rhythm, there is also the need to develop the motor imagination which, on many occasions, will have to replace the concrete realisation of a movement.

But this imagination cannot be taken for granted. It has to be provoked by moments of calm during which you evoke inwardly the gestures, sensations and feelings associated with a particular rhythmic motif. Imagination is a mental faculty. It is therefore normal to build it up through the conscious analysis of experienced phenomena.

2. Dictation

Situated at the height of the difficulties of a music theory course, it should be the easiest part: easier than the readings, which are themselves easier than the rhythmic tapping and all the oral work. The aim of dictation is above all to train students to transform a living, concrete rhythm into the abstract signs of writing. It thus prepares the way for invention and composition.

It is also a means of stimulating and developing the immediate memory of motifs and phrases. Finally, it is a means of checking the level of assimilation of the rhythms studied consciously. In practical terms, it generally proceeds as follows (basic outline). It should include at least two motifs, 4 are sufficient, and later 8 or more to train endurance of concentration.

- The dictation is played in its entirety. The students determine the measure and the numbering. Having heard it once, they can estimate the values involved.

- The pupils prepare the number of measurements needed in their notebooks, to help them write the values in proportion.

- The first pattern is played twice in succession while the pupils listen, beating time.

- Following the repetition of the pattern, the pupils reproduce the pattern and its repetition on a word (pam, ta…) without stopping beating the bar.

- They continue the repetition, but this time internally to reinforce the memory.

- Once they have memorised the pattern, they can work on transcribing it, using the beat as a guide. Ideally, they should write down only what they are sure of, to avoid being influenced by signs already on the paper.

- The first pattern is played back once and followed by the next pattern, which is itself repeated once, then

- Following the repetition of the second pattern, the students repeat it twice without stopping the beat etc…. until the end of the dictation.

- The dictation is played back in its entirety without repetition to allow an overall check of what has been written.

After that, the dictation can be used as a playback, with the addition of various rhythmic modes, tempi, memory playback, etc.

If the dictation has been given over the chords of a cadence, you can then improvise melodically over these chords, keeping the rhythm given, etc….

Clearly, such a process is demanding and can be difficult for many students. That’s why it’s vital that the level of dictation is easy for everyone. As always, according to Edgar Willems, the way things work is much more important than the result.

When the psychological functioning is right, the results follow immediately!

3. Recognising bars and tempi

You also need to be able to recognise and count the bars. For practice, the teacher improvises in different bars and tempi.

The student starts by feeling and beating the tempo, then locating the inspiration marking the place of the last beat and consequently that of the first, and determining the number of beats in the bar. The pendular (2 beats), rotational (3 beats) or narrative (4 and 5 beats) nature of the beat should confirm the choice. Next, he will look for the nature of the division, binary or ternary, to establish the corresponding cipher.

Finally, based on the passing of the seconds, he will qualify the tempi: Andante for 60, Allegro for 120, and the rest relatively.

III – The instrument

With the exception of the voice, because it is inside the body and therefore invisible and impalpable, all musical instruments use the hands and require the harmonious participation of the whole human body. Many instruments also use the fingers and require their independence, even the organist who adds the independence and agility of the feet.

Each instrument requires its own particular technique, different from the others in every detail, but with common points for each family: bowed strings, plucked strings, struck strings, wind instruments, brass instruments, and sub-groups determined by the way in which the sound vibrations are produced: bevel, mouthpiece, single or double reeds, keyboard, mallets.

But no instrument ‘makes’ music on its own! An instrument is simply an object, of more or less complex construction, capable of emitting vibrations that will only be music if the person who produces them has premeditated their meaning and an attentive ear receives them without prejudice to lead them to a sensitive human brain, first and foremost that of the instrumentalist himself…

A – Physical preparation for playing an instrument

All instruments require motor skills and movement, initiated by a rhythmic impulse. Plasticity is the first to be involved. The education of plasticity begins at the 1st level of musical education in the sequence of clapping, in particular with the hands on the table: the quality of the momentum, the precision of the synchronisation of the impact with the voice, and therefore with the guiding thought, the quality of the rebound, which accompanies a long sound or is transformed into a new momentum. The importance of great motor skills and general relaxation of the body, which enables the energy to be concentrated on the impact vector.

Then comes the special work of energising the brain by stimulating both hemispheres in a balanced way (the right hemisphere controls the left and vice versa). Hence the interest in alternating hand claps, and also clapping with one hand, reproduced with the other, and finally clapping with both hands together, stimulating the whole body, activating blood circulation and increasing nervous and muscular tone. During the 2nd degree, the dissociation of the hands is introduced, or more precisely, according to the psychomotricians, the differentiation of the hands, the two being used differently in the unity of an action.

Regular clapping with one hand, to which the other is added from time to time, on command, etc…. During the 3rd degree, the simultaneous clapping of rhythmic modes, already mentioned in chapter B §1, contributes to greater awareness of this differentiation, first at the level of the whole body, then gradually at the level of the fingers for fine motor skills.

This begins with the anatomical naming and numbering of the five fingers, which precedes instrumental fingering. Finger strokes on the table will complement the hand strokes, seeking the same harmony between relaxation of the swing and tonicity of the extremities producing shocks, the gesture always starting from the inside out and not fixed by a quantitative result of the frequency of the strokes.

All gestures and movements practised in large numbers will have their equivalent in fine motor skills. If the image has been presented, experienced and fixed in the memory with all the plasticity required, it will be restored as it is with fine motor skills.

The mind, the spirit, must be at the source of the movement, accompanying it as it is carried out and recharging itself with the energy expended by being receptive to the energy itself.

B – Lively interpretation

After all these considerations, making music through one’s instrument is the infancy of art! But there is still one difficulty to take into account: there is not just one possible plasticity arising from a single living rhythmic impulse. And yet the author, the composer, has generally had a single thought in conceiving his work. What guarantee do we have that we will serve this thought and reap all its benefits? We have seen that there are very few graphic indications and that, in any case, they are very approximate to the physiological gesture they are intended to influence. What remains is a good sense of language and its articulation, caesura and breathing, and a knowledge of the styles specific to each era, handed down through numerous treatises and no less numerous lines of masters and disciples…

“From the heart, may it return to the heart”, said Beethoven.

CONCLUSION

Edgar Willems often left the door open to future discoveries by science and musicologists. A truly encyclopaedic work, scientifically conducted from a variety of complementary angles, his work “Musical Rhythm” could not have been summed up in these few pages.

In particular, he devotes a great deal of space to Greek rhythm, having played a part in its rediscovery in the twentieth century, in his youth. But his main point is that it is not enough to consider the question of rhythm in its full musical and artistic dimension. This is why, for the sake of brevity, I have chosen not to tackle the subject in this dissertation.

At the very least, I hope I haven’t betrayed his thought, whose beneficial breath has made my neurons bubble all the way to the tip of my pen!

What remains is practice, which life renews at every moment, and which allows the rigorous methodological framework proposed by Edgar Willems never to be a straitjacket but a permanent possibility of personal progress in the joyful work with children, an experience that I have been living every day without tiring of for almost 25 years!

“Musical Rhythm” by Edgar WILLEMS

Didactic Diploma thesis by Christophe LAZERGES – 2005